Monstrosity beguiles, for its alienating, otherworldly horror unveils something to the mind that we take great pains to hide in day-to-day life—often, the ravenous ugliness of the systems with which we are complicit and the depths of our own hearts. It is wishful thinking that makes us reduce such things to merely our own psychic projections or to wholly insulated spiritual beings: even when the culturally constructed monstrous reflects our prejudices and evil assumptions, it is in the visage of the demon that inspires us. Yet sometimes the monstrous can be prophetic: when the visionary of Daniel 7:1-14 sees the vision of the four beasts that are judged in the presence of the Ancient of Days and whose dominion is replaced by the supremacy of the one like a son of man, these beasts are obviously not only monsters of chaos but they are also not merely political allegory, either, anymore than the Son of Man himself is reducible to a divine or angelic being on the one hand or to a metaphor for Israel at large on the other (7:16-17). The fright of these empires—and the dramatic establishment of God’s Kingdom—are clear to “Daniel” only through the vision of their animating intelligences: when “Daniel” sees the fourth beast, he remarks that it is “terrible and dreadful and exceedingly strong” (7:7); and Daniel says that “my spirit within me was anxious and the visions of my head alarmed me” (7:15). “My thoughts greatly alarmed me,” he says, “and my color changed; but I kept the matter in my mind,” the apocalypsis or monstrum of the vision cultivating a Saturnine mood of contemplation for the seer (7:28).

Apocalyptic literature is the native home of the monstrous in Early Judaism and Christianity; the genre itself is nothing other than the union of the prophetic and the sapiential in quest for divine knowledge through the imaginal realm, the metaphysically liminal space where monsters reside. So in the Apocalypse of Zephaniah, the seer, upon descending to the underworld, reports:

8 I saw a great angel before me. His hair was spread out like that of lionesses’. His teeth were outside his mouth like a bear. His hair was spread out like women’s. His body was like the serpent’s when he wished to swallow me. 9 And when I saw him, I was so afraid of him so that all the parts of my body were loosened and I fell upon my face. 10 I was unable to stand, and I prayed before the Lord Almighty, “Thou wilt save me from this distress….I beg you to save me from this distress.” (Apocalypse of Zephaniah 6.8-10, in James H. Charlesworth, ed., The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, vol. 1, Apocalyptic Literature and Testaments [New York: Doubleday, 1983]).

The monstrous visage of the accuser frightens and reduces the seer to prostrated prayer to God; but

11 Then I arose and stood, and I saw a great angel standing before me with his face shining like the rays of the sun in its glory since his face is like that which is perfected in its glory. 12 And he was girded as if a golden girdle were upon his breast. His feet were like bronze which is melted in a fire. 13 And when I saw him, I rejoiced, for I thought that the Lord Almighty had come to visit me. 14 I fell upon my face, and I worshiped him. 15 He said to me, “Take heed. Worship me not. I am not the Lord Almighty, but am the great angel, Eremiel, who is over the abyss and Hades, the one in which all of the souls are imprisoned from the end of the Flood, whihc came upon the earth, until this day.” 16 Then I inquired of the angel, “What is the place to which I have come?” he said to me, “It is Hades.” 17 Then I asked him, “Who is the great angel who stands thus, whom I saw?” He said, “This is the one who accuses men in the presence of the Lord.” (Apocalypse of Zephaniah 6.11-17)

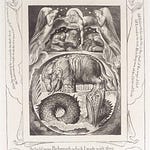

There is a lot of uncanny ambiguity to the scene. The immediate implication would seem to be that the angel Eremiel is in fact the accuser himself, or at least in charge of the accuser, whom the seer witnesses prior to his prostration: where the accuser stood, now stands Eremiel in priestly, royal garments. And in Apocalypse of Zephaniah 7.1-11ff, it seems in fact to be Eremiel (the “he” is ambiguous, but its antecedent would most logically be the named angel) who holds the scroll of the seer’s sins for him to read, before holding another scroll—presumably detailing his good works—on account of which he is able to abandon Hades and set off for heaven in 8.1ff. On this reading—admittedly my own, since no one to my knowledge has made it in print (though I am happy to stand corrected)—the angel is monstrous in visage prior to the fear, prostration, and prayer of the seer, and is only beautiful afterwards; the horror of the accuser is the preface to the divinely beautiful angel. By way of instructive contrast, the Christophany of Revelation 1:9-18—which either parallels, sources, or borrows heavily from Eremiel’s depiction in the Apocalypse of Zephaniah1, and like the manifestation of the accuser, causes the seer to fall down like a dead man (Rev 1:17)— presents the divinely beautiful “one like a son of man” already at first in the high priestly celestial garments, and yet his horrific manifestations as the crucified, the divine warrior, and the eschatological judge are interlaced throughout the book.2 In the “unveiling of Jesus Christ,” moreover, far more monstrous and otherworldly horrors come forth into the light of the seer’s vision: the four riders of the first four seals (6:1-8); Abaddon or Apollyon, the angel of the underworld, and his locusts from hell (9:1-11); the chimaeric cavalry from the East (9:13-19); the sky dragon Satan and the monsters he summons from sea and earth (12:1-13:18); the frog demons (16:13-14); the whore of Babylon and the beast she rides (17:1-18).

The beauty of divine light and the epiphany of evil’s deformation and defeat are seemingly intractable from one another in this literature: to see the otherworld involves beholding monsters, but monsters not wholly other than ourselves, that are instead sometimes other selves. Shadows lengthen before they vanish in rising light; so too the intensification of myth, prophecy, and wisdom in apocalyptic literature as it develops over time throws the monstrous into ever starker relief. That is to say, each new generation of visionaries sees these monsters differently, and yet more clearly, than their predecessors, not by way of a linear progression, but through the layered aesthetics and intertextual artistry of what villainy has been seen before: Dante’s Satan is not John of Patmos’ Satan, nor still yet Job’s Satan, and yet includes and transcends them. The monstrous is woven from our experiences, including our experiences of fear, and experiences—including apocalyptic ones—are transmitted across generations in oral and textual tradition; this is why the visionaries see such closely related and yet such distinct phenomena. And yet, in each case, Satan’s character comes into sharper focus as does the comprehension of Christ: Satan’s very personification and personalization is more possible in light of a more detailed understanding of Christ, not less, since with Christ’s gaze we see beyond the monstrous visage of Satan and what his fallenness reveals—evil’s metaphysical nothingness and destiny to lose—to what his aboriginal essence might be.

The monstrous considered as an essence in itself proposes a dualism which ends up collapsing inward: hence, as discussed in the pars prima, between Greek monsters and Greek gods no insurmountable ontic barrier may be found. Though the Greeks reviled the former and adored the latter, their reasons for doing so were largely pragmatic in character, and so reflect a psychology of religion that is largely mercenary and technical: really, the gods are monsters and the monsters are gods, and it is only we who award them either name. The moral value of the monstrous demonic in Early Judaism and Christianity shifts this dualism somewhat more comprehensibly: the ontic state of the real cosmic monsters proceeds from the darkening of their volitional intellects, and the ravenous terror of their corporeality reflects the dolorous blow their defection from God has effected. Yet here, too, there is a problem. For the parasitic entropy of evil in participated being means that the monstrous cannot always have been so, that its monstrosity must either be an illusion or a misfortune. In se, Satan remains an angel, perhaps the angel set over the entirety of the spatio-temporal material kosmos (he is, after all, the “god of this aeon”; 2 Cor 4:4); his monstrosity reflects a distorted, though still enduring, revelatory power unique to his being, perhaps as the Light-Bearer (Helel Ben Shachar, Eosphoros, Lucifer, and so forth). Corruptio optimi pessima, and all that. But to take this seriously—especially within the panentheistic, panpsychist, and universalist framework that are endemic to the Christian Tradition at its best—means that the mysterium tremendum et fascinans of the monstrous must at some level elicit our curiosity about what, in the eternal plan of God, the monstrous was originally intended to be. Leviathan is after all in turns God’s pet or God’s ancient foe in Jewish and Christian literature; Satan is our enemy and accuser, and yet appears before God in the assembly (or at least did, at one point). God donates his infinite being to these creatures with abandon even in their reckless hunger and destructive intention: for God to be good, that must mean that the core of their being is itself good, the monstrum not of evil’s nothingness but of some aspect of God especially given to them.

We hopefully realize that easily enough when we contemplate the animal world. The zoologically monstrous reflects distinctly anthropocentric concerns and convenience—dinosaurs were monsters because we could not have coexisted with them; spiders are monsters because they may poison and kill us; etc.—yet no sufficiently Christian theologian could fail to realize that every animal without fail manifests something of God and is a good in itself, whose destruction or extinction or elimination for reasons purely of human interest or need is an objective moral evil. The ecological crisis is proof enough that we become what we fear: that the illusion of monstrosity will infect our own spirit if we do not learn to see beyond it. Hence those who fear beasts become most bestial; those who fear demons become themselves demonic; those who fear mental constructs of God that are for all intents and purposes demonic do likewise. Certainly, the mass extinction event that is the anthropocene qualifies as demonic, if anything does.3 Our fears of scarcity, our fears of competition, our fears of lost sovereignty—by fearing them, we bring these very monsters into the world.

“Perfect love casts out fear” (1 Jn 4:18): fear may be where many of us imperfectly begin our loves, but it will consume them if we do not resolve it. Our fears must be confronted: the apocalypticist must descend into hell with all its demons before ascending to heaven with all its angels. The archetypal spirits which present themselves to us in our myth and folklore, and perhaps in our real paranormal experiences (I am no reductionist or materialist), perform in their very monstrosity this tremendous service to those who would be saints: to face our fears, our fears must have faces. Or, rather, we must come to see that we have all the time been poorly seeing their true faces: that until, like the seer of the Apocalypse of Zephaniah, we have undergone some falling down and standing up, some death and resurrection, what is really the face of the angel appears to us as the face of the accuser, what is really the Angel of YHWH appears to us as a demon wrestling in the night, what is really Christ appears to us as judge and executioner. The true resolution of the ambiguity of the monstrous is to be found only here: to see beyond the phantom, to see that the wells of space are full of light beyond the cast shadow of the Earth.

See David Armstrong, “A Kingdom of Priests and Gods: Angelic and Participatory Deification in John’s Apocalypse,” MA Thesis, Missouri State University (2018): 69-72.

David Aune and Craig Koester both think that the garments of the “one like a son of man” in Revelation are not priestly, but they are wrong. See again Armstrong, “A Kingdom of Priests and Gods,” 80-86, and the scholarship referenced in the footnotes there.

Share this post