Bearing dreams to all who listen as he sounds his elfin horn

Where the crystal vapours glisten past the farther hills at morn;

Where the sunset hovers playing on the teeming cottage yard

Till the cryptic night comes straying in a mitre tall and starred.Dreams elusive and uncertain, fleeting as the dying year,

Glimpses from behind the curtain, half to cherish, half to fear;

Memories that charm and beckon, vanished scene and vanished face,

Phantoms past the worlds we reckon, reaching from the wells of space.—H.P. Lovecraft, “October” (1920)

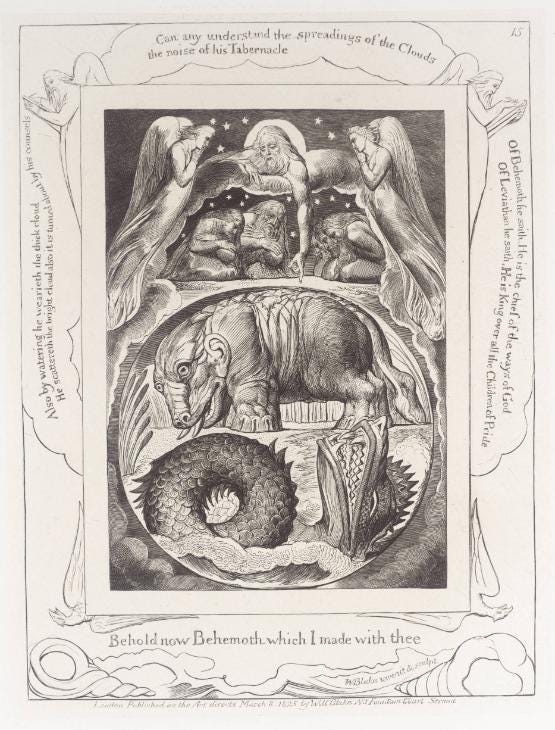

In the earliest layers of the Hebrew Bible, or at least in the vestiges of ancient Israelite mythology that periodically peep through its canonical sheepskin scrolls, YHWH—in persona Baalis, Marducis, aut Iovis—does battle with a sea monster to make the world. This sea monster is variously named Rahab or Leviathan; it is clearly the mythic and literary parallel of beasts like Tiamat from the Enuma Elish, Tannin of the Ba’al Cycle, or Typhoios/Typhon of Hesiod’s Theogonia. “Thou didst divide the sea by thy might,” sings the Psalmist to YHWH: “thou didst break the heads of the dragons on the waters. / Thou didst crush the heads of Leviathan, thou didst give him as food for the creatures of the wilderness” (Ps 74:13-14). YHWH reigns “over surging Yam”—that is, the Canaanite sea god—because he has “crushed Rahab” (89:9-10). There is probably a mitigated, and somewhat retconned, version of this myth in the main creation narrative of Genesis 1:1-2:3: there, God (Elohim this time) divides the waters (a classic act of the watery theomachy; 1:6-7, 9), and is actually said to have created the tanninim, the “sea monsters” (1:21). And this theomachy is repeated, or echoed, or ongoing in YHWH’s battle to establish his sovereignty over the world in and through the people of Israel in their liberation and covenant: hence, the actual context of Psalm 74 is the parting of the waters at the Exodus, which is intrinsically theomachic (Exod 12:12) and which other authors of the Hebrew Bible also invite us to see as a repetition of YHWH’s primordial battle with the chaotic forces of the waters (e.g., Isa 51:9-10).1 The implication is fairly clear: ancient Israelites generally believed in YHWH as a henotheistic king of the gods not unlike Ba’al, Marduk, or Zeus, with whom at least some more cosmopolitan Israelites and later Jews were likely to associate YHWH at the level of hermeneutic and philosophy, if not at the level of actual cult. Like these other gods, YHWH arose to prominence through defeating a chaotic sea monster at the dawn of time—and then continued defeating chaos in the world upon aberrant divinities and humans through Israel’s covenantal saga.

For what it is worth, this imagery was not lost on Early Pagans, Jews, and Christians, even as they moved increasingly towards a classically theistic vision of God. Theomachies simply became the ventures of lesser divinities, angels, demigods, and heroes. The source of Herakles’ veneration for much of the ancient world, for example, was that he had defeated many of the monsters that survived the Titanomachy and therefore enabled the human settlement of the oikoumene; his epic romp of Labors could thus be recast as genuine acts of philanthropia. For Jews, the equivalents of Greco-Roman heroes were often the patriarchs and prophets of Israel’s past, understood at least from the Hellenistic period onward to have been deified to the heavenly world. Broadly speaking, figures like Adam, Enoch, Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, David, and so forth were all understood to enjoy a kind of heavenly existence as gods or angels in God’s court; more specifically, some of them achieved this status through theomachic means. Jonah, for example, was understood by some Early and Rabbinic Jews as having descended into the underworld in the belly of the fish, in order to be designated the one who would slay Leviathan at the end of the world.2

It is for these reasons, pagan and Jewish, that Early Christians construed the significance of Jesus’ death, burial, descent into the underworld, and resurrection as a kind of theomachy. This is already going on in the apocalyptic vision of the woman, the male son, and the dragon in Revelation 12:1ff, and in Jesus’ construction of his forthcoming passion as judgment on the “prince of this kosmos” in John 12:31. The divine warfare of the paschal triduum remained at the forefront of Christian consciousness throughout late antiquity and the middle ages. The Byzantine hagiography for the Paschal vigil on the night transitioning from Holy Saturday to Easter Sunday, for instance, remarks that “Jonah the Prophet was caught, but not held in the belly of the whale. For being an impression of You, Who suffered and was given over to burial, he sprang forth from the whale as from a chamber”; because Christ descended, “Hades was pierced in the heart, having received the One pierced in His side, and was consumed by the force of divine fire.” Hades was a monster: Christ slew it in being slain.

These are fairly standard observations in contemporary scholarship and informed biblical theology. And in our culture, which does not generally have a rich mythology of its own—since all of our most popular myths are outsourced to cultures far more ancient and respectable than our own—the theological move to take this ancient mythology seriously as a kind of theo-history is understandable. There is something engaging and encouraging about the divine warrior, the god who will come to our rescue against the cosmic forces that are too big for us to fathom or do battle with in our human fragility.3 But of course, to take the mythological aspects of Scripture as straightforward history, even as straightforward divine or metaphysical history, is both to misunderstand myth and to misunderstand its possible uses for talking about the extrahuman world.

What I mean is that ancient people were often aware that their myths were not literally true; they were often intolerant of the literalists among them who, allegedly in the name of conservatism and traditionalism, took mythology seriously in the wrong manner; and they often allegorized myth without emptying it of divine content. In the Greek world, this meant that many Greek philosophers did believe in the Olympian gods, even while recognizing them as lesser divinities in a cosmic hierarchy that stretched far beyond them, or symbols of divine principles far exceeding local daimonia, but did not believe in the songs of Homer or Hesiod ad litteram. Among Jews and Christians, this hermeneutic meant definite, clear belief in the reality of the biblical God and of his acts in and through Israel, Christ, and the earliest Christian communities, without, per se, a literal belief in the texts of Genesis 1-11 or even a literal belief in the mythological cosmology that one finds in portions of the New Testament. Some early Church Fathers were, for example, impatient with the notion that Jesus, in “descending” to the underworld, literally went in his soul into the heart of the earth; it was hardly a novel suggestion, having first been made by Plato, that Haides simply means the “unseen,” and refers to a realm quite apart from the one in which we live, though the subterranean or chthonic signifies the unseen better than any other natural phenomenon we know. Likewise, St. John of Damaskos denied that Christ, in “ascending” into the heavens, could literally be found at a point in spatiotemporal matter: instead, the Scriptural language was to be taken as referring to a real event, but one whose ultimate content transcended the limitations of language and could thus only be referenced by a prepositional cosmology that did not literally apply. Reading Scripture rightly to the minds of such authors required an acute sensitivity to the various generic layers of the biblical text, and to the way that significance changes with context.4

The same rule applies generally to monsters: we should seek to get our mythology about them straight, and even to adjust our cosmology to accommodate them should they appear, but above all we need to be sensitive to the ambiguity of their significance to religious psychology. In the Greek world, the monstrous was usually a cipher for what the Hellenic imagination (and the Roman following it) took to lay beyond the power of civilized human control: be it divine, Titanic, or more generally “natural” (whatever that can be said to mean in an ancient context where the gods were part of nature), monsters by their definition exceed human power in a dangerous or volatile way. Monsters are, as Fiona Mitchell puts it, “aberrant bodies,”5 expressions of corporeality that defy the normative expectations of the people who list them in grimoires and catalogues of exotica. For the Greeks, the world in its chaotic state is monstrous, and even its tamed geography is haunted by monstrous spirits. The famous examples here are well-known: Skylla and Charybdis as the Messinian Strait; the drakones said to guard the sacred groves of Greco-Roman myth and religious memory; the margins of maps which promise sea serpents at the recesses of society’s reach. Greek xenophobia was archetypically expressed in the anthropoid monstrous: it is not accidental that when Odysseus washes up on the Isle of the Cyclopes, far at the edge of the archaic Greek mental world-map, its inhabitants are giant, brutish, pastoral, one-eyed cannibals who do not fear the gods. Barbarians were given to monstrous qualities, so thought the Greeks, for any number of reasons, having to do with what they perceived to be poor, mutant, deficient biology, uncivilized customs, poor acquaintance with the gods, and so forth. Yet it is precisely this wild transcendence of the ordinary human norms of safety that makes monsters divine or, at least, the divine monstrous: Polyphemos is, after all, the son of Poseidon, and Typhoios the son of Gaia and Tartaros in Hesiod’s Theogonia; the Medes are barbarians in the Greek imagination, and yet they are the progenitors of magical knowledge, so named for Medea, the granddaughter of Helios and most famous witch of Greek myth; Orpheus, a demigod in most accounts, is Thracian. The gods, too, could be monsters. The Olympians, even in their immortal beauty, were capable of acts of savagery and raw power; reading Hesiod, it seems clear that the main distinction between gods and monsters to ancient minds was that gods utilized their power on behalf of the more vulnerable beings of the kosmos, whose submission they nevertheless demanded, while monsters wielded their power at the expense of the weak trampled underfoot. This is a difference in degree or orientation, not in kind; indeed, perhaps this is half the point of the Theogonia and the Opera et Dies themselves.

Ancient Near Eastern and Mediterranean peoples were not alone in their fear, revulsion, and fascination with monsters, but as one moved farther east some monsters—particularly dragons—acquire a greater capacity for being understood not as mortal enemies but as beings of great wisdom and compassion for humans.6 Dragons do not immediately cease to be adversaries as one moves this direction: Rostam slays the dragon of the plain in the Shah-nameh; Indra slays Vrtra, the dragon of drought, in Rg Veda 1.32; and even in Chinese culture, where dragons are more generally benevolent, Li Shizhen could still write in the Bencao Gangmu that some report that “the dragon’s nature is coarse and violent,” although this is tempered by the fact that “it loves beautiful jade and kongqing stones and enjoys eating the flesh of swallows,” and has fears, like “iron and mangcao herb, centipedes and lianzhi branches, and Five Colored silk.”7 In “The Tale of Tawara Toda,” a dragon in humanoid form requests that Fujiwara Hidesato kill the ancient draconic enemy of the centipede, while Urashima Taro’s refusal of the love of the dragon princess for him results in tragedy.8 More generally across the Near East, India, China, and Japan, snakes, serpents, and dragons have the potential to serve either as agents of evil or as servants of good and mediators of divine revelation:9 the seraphim of Isaiah are likely best understood as flying snakes, for instance, and in most classical Christian angelologies, they inhabit no less than the highest choros of divine beings in constellation around God. Divine serpents likewise served Egyptian deities and a variety of Greek ones, particularly of healing, like Asklepios or Hygieia.10 The lung of Chinese and other South and Southeastern Asian mythologies is archetypically the guardian of auspice, the benefactor of the human and natural worlds. Such beings might still pose a threat to humans by virtue of their austere power, as is clear, for instance, in the liminal allegiances of the nagas and naginis of Indian cosmology; nevertheless, in general, divine serpents were omnipresent in the mosaic of the ancient religions of Asia, Africa, and Europe, and boasted as many helpers as hindrances.

Al-Masudi was thus perhaps correct to write, as he did in Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems, that “God knows best what the dragons really are.”11 And there is indeed, at least to my mind, some legitimate question about whether the monsters of the classical, medieval, and early modern imaginaria are not indicative of some kind of real spiritual menagerie, even if probably not a taxonomy of sarkic creatures. Here, again, the liminal pitfalls of imprecise hermeneutics threaten credibility. On the one hand, many amateur classicists know enough about Greek, Roman, Jewish, and Christian monsters to name them and the lore which surrounds them, but not enough to know that the literati of the late antique and medieval worlds were typically skeptical about the literal reality of such creatures as flesh-and-blood beings already in that era. And if anything, we have more reasons than ancient people did to doubt the dragons of their myths: we know more about biology and ecology than they did, and more about the general history of life and its evolution on the planet, enough at least to doubt most cryptids. And yet, on the other hand, our cosmology is not really so enlightened as we typically imagine such that it has ruled out magic or the spiritual; even at the level of the biological, we also know better than the ancients did the stark, wild diversity of living beings on our world throughout the course of its history. When we dig up dinosaurs, and imagine what they were like, we are not really engaging in anything less intrinsically mythical than what the ancients were engaged in, not least since they too were inspired by the same fossils in many instances.12 Our monsters are arguably less interesting, since we generally assume that they were but dumb beasts rather than magical beings possessed of intent, however malicious, where the ancients typically saw their physical, embodied existence in the mythic past as mere preface to their postmortem existence as hellish terrors or divine interlopers. We today cannot seem to find a use for the monstrous that might bridge the external and the internal.

Even the monsters of our psychological and fantastic fixations are guilty of this kind of reductionism. For William Blake, there seems to be something artistically carnal about Leviathan, who is succeeded in the scale of being by Behemoth, humans, and God; Jung saw Leviathan as the dark maternal, capable of devouring as much as land-based counterpart gives life. The monsters of our contemporary fascination in literature and film—Lovecraft’s Cthulhu and the other Great Old Ones, the kaiju of Japanese cinema of whom Gojira is king, the ravenous beasts of Dungeons and Dragons or the calculating evil of the Mind-Flayer in Stranger Things—all bespeak the evil and might of the monstrous as it lay in wait in the cosmic corners, ever capable of being roused to romp, dared to devour the waking world. And all of these takes on the monstrous are helpful—the monstrous does really reflect the darkness of the psyche; it is intrinsically unlikely, all but impossible, that dragons were simply a now defunct species of organic creature once coexistent with humans, etc.—but there is something missed in them of what Owen Barfield would have called “participated consciousness,” the sense of something outside seeking entrance in. The problem, that is to say, is that we do not realize that while Cthulhu may not be a literal entity in our kosmos, the archetypes that he embodies are spiritually real, and they exist beyond us, in names and forms within our kosmos that we may never know in this life, but which certainly bend their malicious minds towards our marring. There do not need to be dragons for the draconic to be real; because the draconic is archetypically, spiritually real, it can bridge our private projections and the monstrosity of the kosmos around us. Getting our monstrous mythology correct means not only learning to read beyond the zoological monstrous, but to see the phantom which reaches towards us in the monster’s literary image. We cannot seem to imagine that the psychic pathologies monsters represent to us are in fact hypostatized—or natures in quest of hypostasis.

In large part, the modern problem with thinking about the monstrous is due to Christian reductionism about monsters in reception. The monstrous must, Jews and Christians have historically thought, be the product of fallen angels and other divine intelligences whose aberrant intellects on the material world produced such aberrant bodies, or else mere projection of human psychosis. And one or some combination of these have in fact become so identified with this dissolutive genius as to have become wholly monstrous himself; whether that entity is Death, as it appears to be in Paul, or whether it is Satan himself, as it is in the Apocalypse of John, the nadir of the monstrous in a cosmic being opposed to God Christianizes and magnifies but does not ultimately escape the dialectic of the divine and the monstrous, the problem of monstrous ambiguity in the divine realm. The theomachy of God and Christ against the monstrous cannot be the final word on monsters if the God shown in Christ is also the world’s true creator. For monsters also emerge from the wells of space—whether in grotesquely hideous strength or phantom beauty—in order that they might “show”; and so the monstrous must have something to say in the final clarity of revelation beyond a word of contradiction to the goodness and beauty of the divine order.

Continuandum in parte secunda.

See Rachel Adelman, “Jonah’s Magical Mystery Tour of the Netherworld,” TheTorah.com (2015).

For late antique takes on how to read Scripture, see Origen, De Principiis IV, for which the best translation is Origen, On First Principles, 2 vols., ed. and trans. John Behr (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), and Adrian, Adrian’s Introduction to the Divine Scriptures: An Antiochene Handbook for Scriptural Interpretation, ed. and trans. Peter W. Martens (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

See Fiona Mitchell, Monsters in Greek Literature: Aberrant Bodies in Greek Cosmogony, Ethnography, and Biology (London: Routledge, 2021).

On dragons, see Scott G. Bruce, The Penguin Book of Dragons (New York: Penguin, 2021).

Bruce, The Penguin Book of Dragons, 212.

Bruce, The Penguin Book of Dragons, 221-232.

See James H. Charlesworth, The Good and Evil Serpent: How A Universal Symbol Became Christianized (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

On Greek dragons, see Daniel Ogden, Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), especially 310-383; idem, Dragons, Serpents, and Slayers in the Classical and Early Christian Worlds: A Sourcebook (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Bruce, The Penguin Book of Dragons, 205.

See Adrienne Mayor, The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myths in Greek and Roman Times (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011).

Share this post