In the last two Sunday Saunters, I detailed the reasons that I believe in aliens and the multiverse. Theologically and philosophically, my answer to both is common: I believe in a God of infinite, profligate love and creativity, who delights in myriads of beings who come to be and in whom he may come to be, too.

This week, I’m talking about the Imaginal Realm, which I wrote about at great length in October of 2023, in an extended series of ten articles published in October 2023 (here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here). But I should point out that the first serious intellectual exploration of the concept to which I was exposed came from our late, great Buddha, Roland Hart, in Roland in Moonlight (2021), and that David Hart and I talked about it at great length here. Here, I am repeating some of the basic ideas behind the concept, and then riffing on certain conclusions I draw from it.

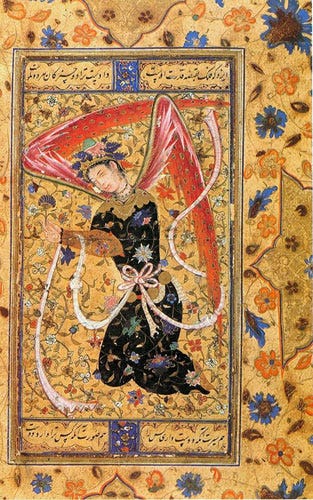

I begin with a quote from Henry Corbin, who describes the concept as it appears in Islamic theosophy:

There is our physical sensory world, which includes both our earthly world (governed by human souls) and the sidereal universe (governed by the Souls of the Spheres); this is the sensory world, the world of phenomena (molk). There is the suprasensory world of the Soul or Angel-Souls, the Malakūt, in which there are the mystical cities that we have just named, and which begins “on the convex surface of the Ninth Sphere.” There is the universe of pure archangelic Intelligences. To these three universes correspond three organs of knowledge: the senses, the imagination, and the intellect, a triad to which corresponds the triad of anthropology: body, soul, spirit—a triad that regulates the triple growth of man, extending from this world to the resurrections in the other worlds.

We observe immediately that we are no longer reduced to the dilemma of thought and extension, to the schema of a cosmology and a gnoseology limited to the empirical world and the world of abstract understanding. Between the two is placed an intermediate world, which our authors designate as ‘ālam al-mithāl, the world of the Image, mundus imaginalis: a world as ontologically real as the world of the senses and the world of the intellect, a world that requires a faculty of perception belonging to it, a faculty that is a cognitive function, a noetic value, as fully real as the faculties of sensory perception or intellectual intuition. This faculty is the imaginative power, the one we must avoid confusing with the imagination that modern man identifies with “fantasy” and that, according to him, produces only the “imaginary.” Here we are, then, simultaneously at the heart of our research and of our problem of terminology.—Henry Corbin, “Mundus Imaginalis I: Nā-Kojā-Ābād” or “The Eighth Climate”

This is not an exclusively Islamic idea, but among the Abrahamic traditions, Islam has arguably retained the most articulate and self-aware notion of it. One could, for example, scan through scores of Jewish and Christian visionary literature, both the literary records of real experiences and literary conceits based on a wide ancient Mediterranean culture of otherworldly apparitions, journeys, and beings, and one would find the Imaginal Realm there, but not named as such: in some way, the Imaginal Realm cannot be named as such until the supreme deity is understood not merely as the biggest, most powerful being in the cosmos but as Being itself, and therefore in need of distinction from all subsequent, lesser layers of reality, including the spiritual and psychic ones. Islam arose at a time when this was normative in theology; Judaism and Christianity assumed their classical shapes right on the cusp of that philosophical development becoming widespread.

Outside of the Abrahamic sphere of religions, one encounters the Imaginal in many other philosophical and religious contexts: as a theme in Greek thought, most emergent in Neoplatonism and Hermeticism; in Indic thought, especially in debates about epistemology, dreaming consciousness, and the identity of self, world, and God; in Chinese thought, in a radically deconstructive attempt to upend what is assumed to be “real” versus what is assumed to be false. Without collapsing all of these various ideas of what the Imaginal is into the same thing (they are all somewhat different), I would pick up on three common themes of them that are relevant to my own construction of what I mean by “the imaginal” in my own theology.

First: the perceptual world created by the senses and the intelligible world engaged by the intellectus purus are mediated by a world in which the corporeal that we perceive with our sense organs and the conceptual that we conceive in the mind are bridged and melded together. Pure thought in its infinite luminosity is, before it is hidden away completely in coagulated matter, refracted into a kaleidoscopic series of colors and forms, if we consider things from the top-down; if we consider them from the bottom-up, then we materially ensconced and enfleshed beings, as we ascend back to the intelligible, we do so through imaginal realms constructed by our material experiences, projected into the psyche.

This is one good way to both hold that lots of people have authentic visionary experiences while also accounting for the clear diversity of those experiences. Even within a single culture, what a visionary sees can change from person to person, place to place, and period to period, or sometimes within the same time period. That’s because no two people’s point of access to the Imaginal Realm is exactly the same, even if we hold that it is in fact the same Imaginal Realm.

Second: the Imaginal Realm is a place of commerce between minds. In Jungian terms, it is the Collective Unconscious, a sprawling psychic landscape in which the experiences and memories and constructs and relationships of the archetypes as humans have experienced them across our history collectively and cross-culturally all indwell. This is also in the ballpark of what Teilhard de Chardin meant when he wrote about the noosphere. And if we broaden our sense of the cosmic Mind to encompass other noospheres beyond this one, other worlds of other minds, intellects, civilizations, and so on, then the Imaginal Realm is not just a space in which we can encounter minds of the past, present, and future of our own world, but others, too. It is in fact a more accessible cosmic highway than whatever interstellar roads of the gods might someday convey us in body to other systems, or whatever dimensional doors afford easy congress with other planes.

I would broaden this point too and say that the Imaginal Realm is a much more plausible and defensible venue for theophanies, angelophanies, and also daimonophanies, for encounters with spiritual and otherworldly beings, than the world known to physics. And it is the world of faerie, of alf and dwarf and drow, of Dream and dalliance. The Imaginal Realm, in fact, as a point of philosophy, is a concept confected to try and explain how it could be that pure immaterial spiritual beings, and God the Absolute, could in any way commune with material beings like humans. Indeed, for Ibn ‘Arabi, the imaginal is the second pillar of epistemology after theology itself: “After the knowledge of the divine names and of self-disclosure and its all-pervadingness, no pillar of knowledge is more complete” (Ibn ‘Arabî, al-Futûhât, 1911 edition, 2:309.17).1 Chittick, explaining the nature of the Imaginal in Ibn ‘Arabi’s thought:

He frequently criticizes philosophers and theologians for their failure to acknowledge its cognitive significance. In his view, ‘aql or reason, a word that derives from the same root as ‘iqâl, fetter, can only delimit, define, and analyze. It perceives difference and distinction, and quickly grasps the divine transcendence and incomparability. In contrast, properly disciplined imagination has the capacity to perceive God’s self-disclosure in all Three Books. The symbolic and mythic language of scripture, like the constantly shifting and never-repeated self-disclosures that are cosmos and soul, cannot be interpreted away with reason’s strictures. What Corbin calls “creative imagination” (a term that does not have an exact equivalent in Ibn ‘Arabî’s vocabulary) must complement rational perception.

In Koranic terms, the locus of awareness and consciousness is the heart (qalb), a word that has the verbal sense of fluctuation and transmutation (taqallub). According to Ibn ‘Arabî, the heart has two eyes, reason and imagination, and the dominance of either distorts perception and awareness. The rational path of philosophers and theologians needs to be complemented by the mystical intuition of the Sufis, the “unveiling” (kashf) that allows for imaginal—not “imaginary”—vision. The heart, which in itself is unitary consciousness, must become attuned to its own fluctuation, at one beat seeing God’s incomparability with the eye of reason, at the next seeing his similarity with the eye of imagination. Its two visions are prefigured in the two primary names of the Scripture, al-qur’ân, “that which brings together”, and al-furqân, “that which differentiates”. These two demarcate the contours of ontology and epistemology. The first alludes to the unifying oneness of Being (perceived by imagination), and the second to the differentiating manyness of knowledge and discernment (perceived by reason). The Real, as Ibn ‘Arabî often says, is the One/the Many (al-wâhid al-kathîr), that is, One in Essence and many in names, the names being the principles of all multiplicity, limitation, and definition. In effect, with the eye of imagination, the heart sees Being present in all things, and with the eye of reason it discerns its transcendence and the diversity of the divine faces.2

In other words, the purity of the divine nature can be partially seen by reason exercised in philosophy, but all philosophy can really bring the soul to know about God is that God is, but not what God is or how God is and must in fact make so many apophatic qualifications about what it means to say that God is that this knowledge simply bottoms out in silence anyway. Philosophy knows God as the One. But the Imagination can know God as the Many, which is how God makes God’s self known beyond reason in the manifestation of the worlds.

For Ibn ‘Arabi, the Imagination is the khayâl, which

accords with its everyday meaning, which is closer to image than imagination. It was employed to designate mirror images, shadows, scarecrows, and everything that appears in dreams and visions; in this sense it is synonymous with the term mithâl, which was often preferred by later authors. Ibn ‘Arabî stresses that an image brings together two sides and unites them as one; it is both the same as and different from the two. A mirror image is both the mirror and the object that it reflects, or, it is neither the mirror nor the object. A dream is both the soul and what is seen, or, it is neither the soul nor what is seen. By nature images are/are not. In the eye of reason, a notion is either true or false. Imagination perceives notions as images and recognizes that they are simultaneously true and false, or neither true nor false. The implications for ontology become clear when we look at the three “worlds of imagination”.

Those are Nondelimited Imagination (al-khayâl al-mutlaq) and ‘âlam al-khayâl, Corbin’s mundus imaginalis,

where spiritual beings are corporealized, as when Gabriel appeared in human form to the Virgin Mary; and where corporeal beings are spiritualized, as when bodily pleasure or pain is experienced in the posthumous realms. The mundus imaginalis is a real, external realm in the Cosmic Book, more real than the visible, sensible, physical realm, but less real than the invisible, intelligible, spiritual realm. Only its actual existence can account for angelic and demonic apparitions, bodily resurrection, visionary experience, and other nonphysical yet sensory phenomena that philosophers typically explain away. Ibn ‘Arabî’s foregrounding of the in-between realm was one of several factors that prevented Islamic philosophy from falling into the trap of a mind/body dichotomy or a dualistic worldview.

The third world of imagination belongs to the microcosmic human book, in which it is identical with the soul or self (nafs), which is the meeting place of spirit (rûh) and body (jism). Human experience is always imaginal or soulish (nafsânî), which is to say that it is simultaneously spiritual and bodily. Human becoming wavers between spirit and body, light and darkness, wakefulness and sleep, knowledge and ignorance, virtue and vice. Only because the soul dwells in an in-between realm can it choose to strive for transformation and realization. Only as an imaginal reality can it travel “up” toward the luminosity of the spirit or “down” toward the darkness of matter.

This is the barzakh. And crucially, in Ibn ‘Arabi’s view, the barzakh contains not only the specifically intermediate space of the mundus imaginalis which mediates between God and everything else, but also the Nondelimited Imagination and, therefore, the physical and sensible world itself, which is but a localized expression of God’s Imagination in coagulated form. Let that sink in: however many worlds exist that can be measured by physics or narrated by history, each of them exists merely as the lowest aggregate of the Imaginal Realm’s infinite possibilities, and is thereby subject to the logic of the Imaginal, though the Imaginal is not subject to the limits of the physical.

There’s a theological path to follow here which would lead us to some revelation concerning God as Being’s Unity and Totality, of which everything else is merely the image; but that is not where I currently want to go. Instead, a third big takeaway about the Imaginal Realm: the imaginal faculty is the most important vehicle for transforming human consciousness. Physics and the sciences give us access to our world, the sensible world, which is part of the Imaginal Realm but only part; philosophy gives us access to the spiritual realm, the intelligible world, but mainly by way of pointing out how far beyond us it is. But those things which cultivate the specifically imaginal faculty within us—deep participation in life, humanities, arts, sophiology—those things are what grant us access to the Imaginal beyond the physical, and therefore which enable our own progress towards the spiritual as well. Philosophy prepares for Sophiology, and not the other way around: the Rational submits to the Imaginal. In terms of our becoming, only the Imaginal helps to propel us upwards towards union with the divine, and only the Imaginal helps make us truly human.

That is not to invalidate or to depreciate the value of the sciences, or of philosophy. They matter, and matter vitally. But it is to say that the senior thing which we must study is the Human Being, who is the key to the knowledge of the Cosmos, and therefore to the knowledge of the Divine. It is also to say that there is an investment of mystical significance in those things that are most profoundly humane and humanistic. Friendship, romance, sexuality, parenthood, family, nature and the polis, reading, writing, cuisine, sport, and simple fun—these basic constituents of life are always potential points of access to the Imaginal and Spiritual realms already, awaiting the release of those hidden energies through our intentional (kavvanah) release of them, perhaps through ritual and prayer but perhaps also simply through our contemplative presence to and with them as modes of the divine presence itself. That’s the most immediate, and perhaps most important, consequence of learning to think imaginally.

I owe the reference to William Chittick’s article here. Chittick, William, "Ibn ‘Arabî", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/ibn-arabi/>.

See fn1 above.

I still think you are failing to give due credit to Roland for pointing us all in this direction.

Reading this felt like someone dipped a quill into the Akashic Records, stirred it into Turkish coffee, and served it with a side of William Blake’s hallucinations. You’re not just writing about the Imaginal Realm. You’re opening the trapdoor behind the world and saying, "Jump in, kids, the angels are weird and the metaphysics are spicy."

Corbin handed us the map. You’re the one handing out lanterns and pointing out the elf queens hiding in the syntax. What a glorious rebuke to the rationalists, who still think the mind is just a filing cabinet instead of a cathedral filled with shapeshifting iconography.

This isn't abstract philosophy. It's an invitation to taste the divine in friendships, in music, in dreams, and in that strange ache we get when reality almost breaks open. Thank you for reminding us that imagination is not fantasy. It is a faculty of communion.

May more of us learn to see with both eyes of the heart, and maybe with the third eye winking just a little for good measure.