What Should Jewish-Christian Friendship Mean?

A Review of Tzvi Novick's Judaism: A Guide for Christians

Tzvi Novick’s Judaism: A Guide for Christians (Eerdmans: 2025) is of the “Introduction” genre, emerging from his class introducing Judaism for undergraduates at Notre Dame. Novick, a Modern Orthodox scholar, frames the book as part tour guide to Judaism for the Christian reader, and part comparative theological enterprise, identifying shared and divergent points with Christian, especially Catholic Christian, theologies. As far as that purpose goes, this book not only does the job well, but probably does it better than the other available introductions I’m aware of in print. There are somewhat more inspiring books on Jewish thought and life, to be clear, including recent ones—Shai Held’s Judaism Is About Love (2024) is a generational masterpiece. But I’d wager that Novick’s book is the best single resource for a general reader to get a grasp on Modern Judaism on the market these days.

Novick’s book manages to weave a more comprehensive, and comprehensible, tapestry for the Christian reader to engage with Judaism as it actually is rather than as Christians have imagined it to be. Christian doctrine about Jews and Judaism changed drastically beginning in the 1960s with the Second Vatican Council, not only in Catholicism but in Protestantism as well. (Eastern Orthodoxy has yet to join the post-supersessionist freight train, and given the nature of how theological change works in that communion, it’s likely as not that it never will.) For Jews, this was a welcome sea-change; among Christians, it is still largely an unrealized aspiration in ordinary parochial contexts, however official a position it as become of the Church.1

Yet though the old veil has begun to fall from the Christian face with respect to the Jewish people and their ancestral religion, a new, more technicolor tapestry, (one perhaps to rival those in the relevant hall of the Vatican) has yet to replace it, and a full-throated post-supersessionism—that is, the position that God’s covenant with the Jewish people has not only never been revoked but is still licit, valid, and effectual today, and even holds the pride of place in God’s affections—has not yet become normative doctrine in Western Christianity, at least at the levels of homiletics and catechesis where it matters most. It has no small number of advocates, Jewish, Christian, and, more marginally, Messianic Jews, in academia; but it has yet to receive an official, articulate expression with teeth in any Christian confession. What Novick offers through the courses he teaches (at one of America’s most decorated and storied Catholic institutions), and in this book written for Christians, is an introduction to Jewish belonging, behavior, and belief that helps Christians, at least, understand better what they’d be signing up for were they to adopt so strong and clear a stance.

In a Preface and Seventeen Chapters—a nod to the Shemoneh Esreh, I idly wonder?—Novick expends five on the questions of the Jewish-Christian relationship, historic and contemporary, descriptive and theologically prescriptive (chs. 1-5); three on the relationship between God, Israel, and gentiles as constituted by Torah (chs. 6-9); three on the Jewish ritual, liturgical, festal, and vital cycle (a familiar topical structure of “Introduction to Judaism” books, but treated succinctly and originally here; chs. 10-12); and five on theology, including the role of the State of Israel in Modern Jewish thought (chs. 13-17). Each chapter includes a “Further Inquiry” section, with a short bibliography on the topic at hand, and guided questions for group readers, which shows a pedagogical heart; as a teacher myself, I’m a sucker for this kind of thing.

But Novick does not merely describe Judaism, or the Jewish-Christian relationship: what is unique about the book for its genre is what Novick accomplishes in the way of the prescriptive and the speculative. An insider to Judaism, Novick introduces the Christian reader not merely to the ancient sectarian divides they will have heard about and only half-understood in other contexts, but more importantly to major voices in Modern Jewish praxis and theology, and in so doing gives a texture, a depth, and a variety to the Jewish experience that is as a rule impossible to find in a stereotype. By doing so, he offers to Christian view how he, as a Jew, reasons through current Jewish pluralism to his own positions in Modern Orthodoxy, including on the new relationship between qahal Yisrael and ekklesia. In the process, then, he also helps the reader see Judaism’s current vitality, intentionally contending with reductive Christian stereotypes that either assimilate Modern Jews to ancient ones or one or both to biblical Jews, including the New Testament’s Jews.2 Humans, including Jewish humans, are instead complex: defined by idiosyncracies, variety, disagreement (in Judaism’s case, lots of disagreement—literally, in fact, disagreement itself as a religious virtue!), and pluralism.

In Judaism’s case, its history with Christianity largely being constituted by Christian stereotyping, Novick’s offer of a path to understanding what Judaism is and is for is not only appreciable for its erudition but also for its manifest generosity. It is not, in general, the job of the put-upon party in a toxic relationship to explain themselves to the aggressor,3 much less over and over again, with greater and greater patience; that there continue to be Jewish intellectuals willing and capable of graciously engaging Christians with a tour of Judaism is, on their part, sincerely admirable. Novick at no point demonizes his would-be Christian interlocutor either, nor assumes that some corporate guilt infuses the Christian reader or student of Judaism with the personal culpability of past generations of Christians, Christian actions, and Christian teaching; nor does he assume out of hand that Jews could have nothing useful to learn from the Christian Tradition theologically. All of this is admirable, charitable even, beyond what I, as a Christian, would say Christianity itself really deserves.

Some of the most interesting parts of the book are not only where Novick points out the differences between the developed shapes of Christian and Jewish theology, nor even where he points out those specialized instances in which Christians have preserved a datum of Jewish faith or culture that, by their reception of it, has fallen out of the normative spectrum of Jewish belief, but rather in those matters where Christianity has something to offer Judaism, and where Christians might justly consider revising their own practice and thinking by reference to the Jewish Tradition. It’s an ecumenism of mutual exchange that Novick envisions. On the former point, Novick mentions a couple of times that Christian thought about matters like grace and faith, while drawing from Jewish roots, offer contemporary Jews, for whom these are often dead categories, new and helpful tools for thinking through matters of faith that the Jewish Tradition itself does not emphasize as strongly. Philosophically, he admits that the classical Rabbis, and thus the halakhic foundation of Rabbinic Judaism, have passingly little interest in philosophy as a tool for thinking about God, and thus that Christian philosophical resources, just like the Islamic ones from which medieval thinkers like Maimonides benefited, are of use for Jewish theologians today. (The traditional statement that Neoplatonism is the philosophical theology of all three Abrahamic faiths is right, but it was not fully true until the Middle Ages.) As a Christian whose Christianity is partly predicated on the beauty of Christianity’s philosophical and mystical theologies, I find the notion that these are things Christianity can share with Judaism, rather than that divide Jews and Christians ontologically, exciting.

This is not to say that I always agree with Novick on where the boundaries of sharing ought to be, even though I respect his right (and the broader Jewish community’s right) to set them where he feels comfortable. Exempli gratia: Novick points out in passing, for instance, and in the scholarship he cites on his section about Hasidism, that Christian thinking about the mediation of Christ was, however implicitly, influential on the formation of the concept of the tzaddik and his associated powers; he cites both Michael Wyschogrod’s work on incarnation as a potential Jewish theological concept and Shaul Magid’s work on incarnational thought in Hasidism in defense of incarnationalism as a potentially Jewish idea. But both take a much more radical perspective than Novick, who maintains that, ultimately, incarnation is not a possibility in the Jewish worldview, in any way. I think this is wrong, basically, not just for reasons of philosophical theology (once what is being claimed by Christianity in the Incarnation is rightly understood), but also for reasons that have to do with the history of Jewish religion itself (incarnationalism has deeper roots in Israelite religiosity generally than Novick admits). But it’s also not for me to tell Novick how to construct his Judaism, and I also think it shows a fruitful openness to engagement, even if Novick feels cautious about how far that engagement can go.

What about Christians? What can we learn from Judaism? Christianity, Novick suggests, could adopt Jewish observance of the Sabbath, acknowledging both that Sunday is not the Sabbath as well as that most Christians no longer regard Sunday as a day of rest anyway, but that Judaism’s Sabbatarian practice results in a profoundly sacred and humane practice at the heart of Jewish life. He also makes the surprising suggestion that Christians, long the only Abrahamic faith to be relatively unrestrained in culinary affairs, could start observing the dietary laws; but he spends little time elaborating on why or how they might go about doing so, and potentially little awareness of the way that the lack of dietary law functions in Christian self-definition.

I can only speak for myself, really: it matches my personal temperament both to consider a Sabbatarian Christianity and to suggest it, at least for the shock-value if not for the experimental restorationist quality. As for kashrut, I’m more indifferent: it’s an unrealized spiritual goal of mine to one day go veg anyway, but if I’m going to eat meat, there’s frankly too much non-kosher Italian food for me to savor the notion. (Also, as a toddler dad, the idea of keeping my kitchen and cookware consistently hakshered is a non-starter.) Moreover, and this could be the specifically Modern Orthodox position of Novick showing through here, but my experience with pluralistic Jewish communities (having taught in a Jewish day school for two years) is that relatively few Jews, of whatever sectarian identity (including many of the Orthodox!), keep fully kosher homes or lifestyles.

There are other, more ethos-oriented changes Christians might consider, per Novick. In a daring reversal, for instance, Christians might follow the Jewish Tradition’s privileging of halakha above aggadah, and Christian canon law could become the essential study of lay theologians and parochial priests. Here, I’m intrigued by the idea—at least its moral, social, and ascetical components—but I’m relatively disinterested in legal minutiae, myself, and I’m not sure that most people of any religious persuasion really are, even while realizing that it’s a rabbinic ideal and that “legalism” is not an inherently bad thing. Christians could also consider respectful ways of entering into Jewish festival time, and given its connection to natural cycles, might well reconsider the role that nature plays in their theology, comparatively and collaboratively with Judaism, where philosophical reflection on nature is not absent or unimportant but certainly less regulatory than in Christian theology. These are interesting proposals: however workable any of them are, I appreciate Novick’s bravery and creativity in fronting them.

On the State of Israel—as Novick acknowledges, the most controversial topic the book treats—he takes a centrist, somewhat open position. If Jews and Christians are now going to be friends, and even religious siblings, he insists, then two things should be true about their dialogue around the State. First, Jews should be able to count on Christians to basically support the concept of a Jewish homeland in Palestine and to avoid arguments and criticisms that verge on antisemitism or raise the specter of theological anti-Judaism, which both conservative and liberal Christians often do, in their discourse about the Israel; but second, Novick at least suggests that Christians should be able to do what good friends do, and offer charitable criticism of the State on both broadly secular principles of modern liberalism and human rights, on the one hand, and on the specifically religious grounds of the shared moral and theological tradition of the Hebrew Bible, on the other, when it comes to government policy and military action. Novick also insists that both things are possible regardless of the specific theological commitments of either Jews or Christians to the notion that God’s gift of the Holy Land is in any way permanent or ongoing: there is a way, in other words, to embrace a non-theological “Zionism” (bracket for a moment the complications of that term) rooted in a purely secular desire to support the Jewish people’s right to self-determination, even if Christians conclude either that God’s gift of the Land to the Israelites is conditional or concluded.

Novick acknowledges that he treats this topic after October 7th, and in the midst of the Gaza War, both of which make these desiderata much more complex than they at first appear. I’ve had to come back and edit this review (6.17.2025; 7.3; 7.7) in light of not only the increasing carnage in Gaza but also the Israel-Iran War. What follows is, I hope, a charitable but also critical attempt to meet what he expresses on behalf of Jewish dialogue partners with Christianity from a Christian point of view.

First, yes, I would like to think that Western Christians, and especially the Catholic Church, can play the role of friend—and therefore, also, of constructive critic—in the evolving Middle East crisis: to Jews and Muslims alike; to the State of Israel and to its neighbors alike; while standing up for the interests of Middle Eastern Christians and the human rights of all people alike; without either descending into antisemitic rhetoric (questions about Israel’s “right to exist” are infrequently meaningful or constructive,4 and the line between anti-Zionism and antisemitism can be quite thin5) or into propagandistic sycophancy (criticisms of the Israeli government, its policies, its military, and their activities, especially with regard to the Gaza War and now the Iran War, are all, in that way, legitimate). I’d like to think that the Church, in other words, can advocate what used to be called “liberal Zionism,” which can take a variety of forms—a binational single state solution, a two-state solution to guarantee Palestinian self-determination, etc.—while also insisting on some common bottom lines: the defense of human rights for Palestinians, an end to violence, war, discriminating policies of occupation and dehumanization, illiberalism, the preservation of Jerusalem and its holy places especially as commonly sacred to multiple faiths, and so on.

This is, I fully admit, a centrist position, and so too moderate to please either far-right actors in either the Jewish or the Christian communities whose sympathies are exclusively pro-Israeli, or far-left actors whose support for Palestinian liberation excludes any recognition of Israelis. But I’d like to think that the Church can do this with some chutzpah, too, acknowledging that a political and religious vision which has room for everyone, which is essential to Catholicism, is inevitably going to upset someone.

But second, and this is a real caveat, for Christians to be able to be that friend, the current moment, in which the death toll in Gaza exceeds 100,000, mostly civilians, calls on Christians to insist that the right to life, self-determination, and flourishing of the Palestinian people must be as non-negotiable as that insisted on for Israelis; and so, immediate and permanent ceasefire in exchange for the return of all remaining hostages, allowance for aid without threat to life, rebuilding of Gaza, the path to a Palestinian state led by the PA, in the West Bank and Gaza, alongside the State of Israel in exchange for the exile of Hamas, with a coalition of Arab states as intermediaries, is the clear short-term way forward. From the Church’s point of view, internationalist diplomacy must prevail over the option to resolve regional instability through totalizing violence or acts of collective retribution. For Christians to be friends of Israel cannot and should not mean that they are not also friends of the Palestinians; especially, expectations that it would mean so of Catholics are simply unreasonable, for many Palestinians are Catholics or belong to Churches that Catholics acknowledge as sisters in Christ. For Christians to be friends of Israel cannot come at the cost of Christian championship for the Palestinian cause. Christian integrity means advocacy of both and simultaneously a willingness to criticize—even our friends. But it also has to mean proportionality to advocacy, and in this moment that means agitating for ceasefire and aid to Gazans and pushback against settler violence in the West Bank first, because this violence is current.

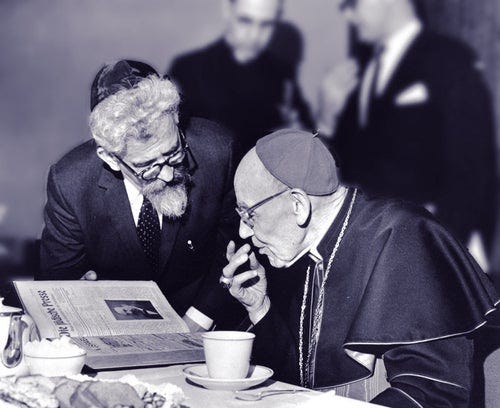

The living image of the Catholic response to the Middle East conflict would be someone like Cardinal Pierbattista Pizzaballa, Patriarch of Jerusalem: offering himself in exchange for the Israeli hostages, as well as agitating for an end to the Gaza War and the suffering of innocents. It is a life of insistence on human dignity as something universal and non-abrogated by the political needs and conveniences of different sides. This insistence does not look past the horrors of October 7th, nor cease to call for the remaining hostages (53 in total, 23 of whom are still alive) to be returned: no Catholic following the Church’s teaching consistently can accept, much less praise, the villainy of Hamas, nor fault in principle the right of Israel to defend itself against Hamas. But the Church also cannot fail to countenance the absolute hell of the Gaza War on Palestinian civilians, which has been waged far in excess of any legitimate right to self-defense. Likewise, with respect to Israel and Iran, the Church does not overlook that a nuclear-armed Iran is bad for world peace; but also does not thereby justify the deaths of Iranian civilians by American bombs shot from Israel, or by American bombs dropped on Iran. The Church knows, and insists, that only diplomacy will make us safer.

In the era of Leo XIV, Catholics in particular can only uphold la pace disarmata e disarmante, the path of peace through dialogue. It is not a cheap peace, but one composed of hard truth and costly reconciliation, for this is the kind of peace Christ offers. Perhaps this will be dismissed as unrealistic by our dialogue partners on all sides, and perhaps even by some of our own co-religionists; perhaps it will be pointed out, correctly, that we have often enough ignored that standard when it was our turn to use power to get what we wanted; and yet, that is our religion.

This answer is unlikely to satisfy a number of Israeli and American Jews—though it does correspond more or less to the perspective of the Jewish Left both there and here, and many public-facing center-left Jews in the United States have made this their position. Christians should resist the temptation to ignore the fact that Israel is currently ripping the Jewish community itself apart, particularly in the United States, as the liberal values with which most Jews here are raised are offended by the actions of the State, despite the education about the State that most Jewish institutions of whatever sectarian identity espouse. Among Jewish theologians, there’s a growing, but not unanimous or dominant, preference for Diasporism; among younger Jews in Conservative and Reform communities, there’s a massive divide between them and the leadership of traditional institutions like synagogues and Jewish federations. Whatever opinions any Christian, myself included, forms about Israel, there is far more dispute within the Jewish community than we realize.

This answer is also unlikely to satisfy a fair number of Middle Eastern Christians and Muslims.6 Here, realism means acknowledging that there’s a difficult confluence of interests clashing into each other for Christians who wish to be good friends to Jews and therefore friends and constructive critics to Israel. On the one hand, the Catholic Church has committed itself to the new relationship with the Jews; on the other hand, many Palestinians are its Christian children and siblings; and even if they were not, Catholic teaching on the sanctity of life would still call for intervention, restraint, respect for their human dignity, peace; and then again, Jews desire Christian and Catholic recognition of Israel as part of the new relationship and the theological dialogue to which Catholics are committed. Simply put, some of that has happened: the Vatican recognized Israel formally in 1993; insofar as Vatican diplomacy reflects Church teaching (which is a tricky proposition, but I’ll roll with it for a second), Catholics recognize Israel as a legitimate member of the international community. For Catholics to also insist on Palestinian rights does not upend that recognition, unless recognition is assumed to mean total affirmation of everything the other partner in the relationship happens to think, say, or do.

Israeli and non-Israeli Jews may somewhat justly feel they are owed deference on affairs of the State of Israel by Christians. It would be fair for Jews to ask, for example, why the Church did not, historically, advocate for them with the same vigor with which the Church feels it must now advocate for the Palestinians—indeed, why the Church bullied them relentlessly up to modernity, paved the way for the worst tragedy of their entire history, turned a blind eye to it while it was going on, only to now critique them. The Church bears a nonzero amount of responsibility for the situation in the modern Middle East, just as it does for the Shoah and all that has followed from it regarding the State of Israel. But it does not follow logically that because the Church persecuted Judaism in the past that it can have nothing critical or prophetic to say now about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, or about how Israel is being run by the Netanyahu administration in particular, or about the actions of the Israeli military in the present conflict. Catholic fidelity to the Gospel and its good news—La pace sia con voi!—is triangulated between these various factors, and it is indeed alienating to walk the middle road in a world that is addicted to the highs of polarization.7

This is something the Church is called on to say now, not least because of her own past of preaching corporate guilt. There can be no true, lasting peace as long as we think, speak, and act in the logic of corporate guilt. Is this not the universal, Catholic meaning of the Christian insight reached by repentance in Nostra Aetate and since about Jews and Judaism: that whatever Jewish involvement there may have been in the death of Jesus, it cannot be affixed to all or even most Jews, then or now, and so cannot serve as the grounds of religious or ethnic bigotry, charges of deicide or obsolescence, or the justification for violence that have been the traditional ingredients of antisemitism?8 Is not the very point of thinking about a “new relationship” between Jews and Christians that the old model of a religious zero-sum game between the two of them is illegitimate, that large blocs of people cannot be reduced to singular representatives, imagined or real? Millions of Israelis and Diaspora Jews are not Netanyahu and his cronies; most Palestinians are not Hamas; most Americans are not Trump; most Iranians are not the mullahs. Perhaps it is too little, too late for the Church to say so now; it must do so all the same. This does not, I think, undermine the friendship Novick wants, but should be constitutive of it: again, good friends tell the truth.

Turning from the political back to the religious, while acknowledging that they are not entirely separate, we might ask what enables the new relationship between Judaism and Christianity theologically within each tradition. Novick begins by tracing the rise of post-supersessionist scholarship and theology in Christianity as the key that has unlocked the new phase of Jewish-Christian accompaniment through history, as the Catholic Church especially has moved closer and closer to a full affirmation of Judaism as a divinely willed and permanently valid religion in covenant with God. The Church has yet to make this its dogmatically binding teaching in a document stronger than Nostra Aetate, but Novick rightly sees it as the overall trajectory of postconciliar teaching on the subject.

The post-supersessionist Christian ideally embraces two additional propositions as a result. First: Christian mission to Jews is unnecessary, counterproductive, and harmful, since God wills there to be Jews and a visibly, distinctively Jewish community in the world, and while regrettable, Judaism and Christianity have formed partly in contradistinction to each other, so to encourage a Jew to give up Judaism for Christianity is providentially misguided. But, second, if a Jew should come to faith in Christ, the post-supersessionist should insist that he keep a life of Torah, and a post-supersessionist Church ought to mandate it in the appropriate manner: being Christian ought not to be in conflict with being halakhically Jewish and with continuing to practice and transmit Judaism to new Jewish generations.

Here, I agree with Novick but I have questions for him. By what competence, for example, could Rome claim to interpret Torah, or to direct the Jew who comes to faith in Christ to the appropriate halakhic authority? As a Modern Orthodox practitioner, I’m sure that what Novick means is that, ideally, Christian Jews or Jewish Christians (or Messianics? What do we call these people?) would keep (Modern) Orthodox observance. But collectively speaking, Modern Orthodoxy is a minority of world Jewry, and its halakhic stipulations and culture are as alien for many Jews as Christianity is, especially for the kinds of Jews most likely to become Christians. At the level of theological method, actually, Catholicism is a lot more like the Conservative/Masorti movement than like Orthodoxy, in that it allows for traditional observance to be in dialogue with modern science, scholarship, and philosophy in its theological outlook, and to affect observance too; but like any other religion in the modern world, Catholicism is also a community with a vast divide between the practice encouraged by her official leadership and that of her ordinary laity. To weigh in on such matters as Torah observance for Jews-become-Christians effectively, the Church would require that the Jews becoming Christians would be themselves thoughtful Jewish practitioners capable of good halakhic reasoning on their own or coming with their own halakhic authorities the Church could recognize—which is rarely the case since, otherwise, they’re unlikely to be the sort of Jews who would become Christian, and moreover, the Church then risks alienating its Jewish dialogue partners who don’t belong to that halakhic tradition that it acknowledges or permits within its own ranks.

Conversely, Jews who become Christians could only realistically be expected to keep practicing Judaism if, from the Jewish side of the equation, conversion did not mean sociological death in Jewish communities. But for the most part, Jews who become Christians are barred from full participation in Jewish communities and Jewish life, are considered apostates from Judaism, and are often not considered Jews at all. I have trouble seeing what the incentive would be for a Jew who, knowing all of that, is still willing to become Christian, to continue practicing a Jewish life after doing so. Paul Griffiths’ advice, that a Jew considering conversion should be dissuaded by the Church, seems more practically apt to me, even if, in principle, I see no reason that Jews and Christians should have to be reified opposites. At least, unless or until the Jewish community at large becomes comfortable with the notion of a dual Jewish-Christian identity, which seems highly unlikely to me in the near future, I don’t know what else the reasonable and humane option would be.

A potential middle ground here are Messianic Jews, on whom Novick spends extremely little time other than to note that they are marginal to both Jewish life (all Jewish communities regard them with suspicion and reject the authenticity of their Jewish identity or at least praxis; they are mentioned with extreme caution in both of the halakhic manuals, for example, of the Conservative and Reform movements) and Christian communities. Of interest, he does note that one of the primary problems with this tradition is that it is still beholden to the evangelical Protestantism in which it first evolved, despite the efforts of respectable Messianic scholars like Mark Kinzer or David Rudolph to move it (however far) out of those paradigms. I’m sure Novick has no desire to countenance a form of Judaism that proclaims Jesus as a or the Jewish Messiah or belief in a Trinity or the Incarnation, and don’t mean to suggest that he should. I am curious, though, if the constructive critique does not occur to him that has occurred to other Jewish interlocutors with Messianics, that if Messianic Jews want to be taken seriously as Jews by other Jews, then they have to actually observe, and they have to accept converts and hold those converts accountable to Torah—that is to say, to be Messianic Jews, not Christians with half-understood Jew-ish aesthetics. This would open up a whole other can of worms for Messianic-Christian relations, of course.

These are the options then for how Christians should rethink Judaism; how should Jews rethink Christians and Christianity? As Novick explains, Jews are relatively new to the discipline of forming a theology of world religions, a domain traditionally of Christian theologians.9 Jews generally do not think the human race needs to be saved from apocalyptic forces of Sin and Death (though some Jews, like Paul, have historically believed so), and also do not think that the whole world needs to become Jewish (though again, some Jews previously have hoped so)—indeed, most would not welcome it. Modern Judaism is much more self-consciously universalist in these respects than Christianity: every human stands in relation to God and, by the embrace of the Noachide laws (often summarized as Hermann Cohen’s “ethical monotheism”), can earn a place in the world to come. Unlike traditional Christianity, then, Jews do not feel a missional urgency about the world’s religions. Modern Judaism often broadens this into a pluralist theology of religions: every religion is a legitimate relationship to God, as far as it goes, while making room for the special covenantal relationship of God and Israel. Again, this is only a recent take in Christian theology.

But this perspective raises unique questions about Christianity, since it too is a religion, but claims, uniquely among non-Jewish religions at least, to participate in something of Israel’s relationship to God. Novick opts for the old Maimonidean view that Christianity and Islam are providential preparations for future messianic redemption, but goes a step further and offers Christians a median place in the trifold Jewish theological conception of the people, the Torah, and their God: namely, Christians are gerim, not in the rabbinic sense of “converts” but in the biblical sense, as “foreigners” or “resident aliens” that have attached themselves to Israel’s God and at least some of Israel’s laws and, hence, to the (halakhic) people of Israel, belonging to it in some way even if they do not fully belong to it as Jews. This is very generous, similar to some Christian models of Christian identity,10 and on the ground, though it is not the formal mentality of most Jews, it has been my informal experience in synagogues and Jewish spaces that I’m welcome as a part of the community without being a formal member, so to speak.

And yet, on both of these counts—Maimonidean Christianity as praeparatio messianica and Christians as gerim—questions linger. Perhaps Novick has thought about them, and perhaps he hasn’t; but I’d be interested to hear him hold forth on them either way. For instance: if Christianity is preparatory in any way for final redemption, and if Christians do indeed draw as close as possible to the covenant between God and Israel without fully joining it, then it is hard to think either thing true, finally, unless in fact Jesus of Nazareth and his apostles were possessed of at least some legitimate divine inspiration, and if the disciples’ experience of Jesus’s glorification was not in some way true, as the catalyst for God drawing the nations closer to Israel as Christians (and perhaps later as Muslims, too, insofar as Christianity influenced the rise of Islam). Pinchas Lapide took this position; is it workable for Jews today? Especially if Judaism takes the role of Christianity among the nations of the world to be a providential choice of divine grace—as Michael Novak rightly insists, Christianity has brought worship of the God of Israel to the whole world, far in excess of the historical reach of either ancient kingdom of Israel or Judah or of Judaism itself—then while Judaism could in that respect make legitimate critiques of the Church’s understanding of Jesus or other elements of its theology, nevertheless, it seems incongruous at best for God to have done so on the basis of an outright lie. Jewish scholars have already reclaimed Jesus in a historical sense; to what degree, if any, can Judaism re-receive Jesus as a figure of religious importance? Martyr? Sage? Prophet? Rabbi? Tzaddik? “Failed,” but not false, messiah, per Yitz Greenberg? Individual Jewish theologians sometimes have reconceptualized Jesus in these ways, especially since the 19th century; but this newer, revisionist take on Jesus is the domain of academics, not of ordinary congregations or their rabbis.11

Especially, this discourse has not yet matured to the point of a bridge that would acknowledge the special status Novick ponders for Christians as gerim, who may in some circumstances feel compelled to become Jews. Could Christians be acknowledged as gerim without having to abandon their Christianity, just as Jews, in theory, could keep practicing Torah even while believing in Christ? Maybe these are possibilities only an academic could imagine, but they are worth imagining, even if only to find out why they might not work.

Why expend so much time on these questions of the interstices—the crevice between the diverging paths of Judaism and Christianity through the cavern of history, rather than on the paths themselves as they are now visible to one another? There’s a relatively simple reason, actually: knowledge is love in potency, and love is knowledge actualized through communion, which itself culminates not merely in being with but in becoming the beloved, “one flesh.” In one version of interreligious dialogue and interfaith relations, we settle for tolerance: tolerance is certainly better than intolerance, and in many cases in this world it is going to be all that we can justifiably manage to do. But the more deeply we know the Other, the more deeply we will come to love the Other and, therefore, experience the desire to unite with them: it is impossible to truly know and not truly love, and more impossible still to truly love and not wish to become.

Speaking from my own side, Christians who really come to know Judaism will come to love it and therefore, however implicitly, wish for unification on some level. That this is not possible in all ways, and should not be pushed for out of respect for Jewish self-determination, Christians will have to accept. But likewise, and here I’m speculating, I cannot see how a coherent Jewish theology of world religions that still holds some form of Jewish eschatological outlook about the future unity of humanity in the worship of God and moral, as well as international, peace will not eventually have to face the question of how Christians, qua Christians, could find their place in Judaism; or at least, how Christianity (and Islam, too) will find itself in the Mes. I suspect billions of Christians and Muslims up and abandoning Jesus and Muḥammad as pretenders is as hard a sell as the idea that the world’s 15.2 million Jews would find simply converting to either tradition an existentially satisfying prospect. If we reject assimilation and annihilation, then we should not settle for mere tolerance: there is love, and unity, somewhere beyond it, even if we will not experience it until the eschaton. Theology allows us to bridge that temporal gap by dreaming, if not always by doing.

Tzvi Novick. Judaism: A Guide for Christians. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2025.

But we should not be too sanguine about the new relationship, as Karma Ben-Johanan, Jacob’s Younger Brother: Christian-Jewish Relations After Vatican II (Cambridge MA: Belknap, 2024) cautions.

See, recently, Sarah E. Rollens et al., Judeophobia and the New Testament: Texts and Contexts (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2025).

I would still basically describe the history of the Jewish-Christian relationship this way; but it is worth drawing attention to a recent argument made here, about the violence that Christians have received at the hands of Israeli settlers, and enduring attitudes of anti-Christian antagonism in contemporary Orthodoxy.

What state has the abstract “right” to exist? By the standards employed by this rhetoric as applied to Israel-Palestine, certainly not my own, Missouri, nor the federation to which it belongs, the United States: both sit on stolen land populated by the descendants of migrants whose ancestors massacred the native inhabitants and used chattel slavery to build wealth and power. But the fact is, these things exist now, and dismantling them to do justice on behalf of previous victims would create as many problems as it would purport to solve. Nation-states are constructs of relatively recent political history, which craft fictional histories that bind together diverse populations sharing the same geographic area and put them into competition with other such populations in other places, and reify perilous boundaries between them. And also, nation-states, at this point, exist, they are how most of the world self-organizes and operates, and the revolution which would dissolve and succeed them with more rational and moral forms of politeia would not be painless, and the vacuum not easily re-filled with something better. So, at least for me, paraphrasing Francesca Albanese, the question of whether Israel has “the right to exist” is irrelevant: it does exist, it enjoys certain rights and privileges as a result of that existence in international law, and the more appropriate question concerns how we can extend the same dignity of self-determination that a state affords to the Palestinians, especially so as to urgently offer them the same rights and privileges for the protection of their civilian population.

I say “can be” because there is a growing chorus of Jewish scholars, communities, and organizations in the United States that are moving if not towards a full-blown anti-Zionism than at least towards a Zion-skepticism or a post-Zionism, which can take various forms. There is the inherent Diasporism of Shaul Magid, The Necessity of Exile: Essays from a Distance (Ayin Press, 2023), the deconstructivist approach of Daniel Boyarin, The No-State Solution: A Jewish Manifesto (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023), and most recently the historicist relativizing of the State in David Kraemer, Embracing Exile: The Case for Jewish Diaspora (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2025). It is not, for me, as a Christian, to tell Jews what to make of this Jewish scholarship on the halakhic and theological relationship between Judaism and the State of Israel, but it is licit for me to acknowledge, minimally, that these too are Jewish voices.

Here, too, the Church is internally divided. The new path with Jews and Judaism is largely the product of the Western Christian context: Eastern Christians, often living in Arab countries and in the Palestinian territories and directly affected by the birth and rise of the State of Israel, have always remained somewhat dissident on this topic since the Second Vatican Council. On the one hand, this expresses the very real pain and suffering that many Arab Christians in particular have experienced in the wake of the 1948, 1967, and 1973 wars and the more recent decades of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and the correct observation that Catholic teaching on life and politics does not exempt anyone or any entity, including the Israeli State. And, on the other hand, it’s not infrequent that this rhetoric which one finds among both Christians and Muslims of Middle Eastern descent often ends up indulging in excess that verges on or sometimes is antisemitic. The counter-histories this discourse produces is exemplary here. One example would be Nur Masalha, Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History (IB Tauris, 2018. The larger quest of the work, to claim that Palestinians have an authentic, indigenous connection to the region, is a legitimate one and it is well-argued. But in pursuit of that quest, the book makes the erroneous claim that Ancient Israelites and Judahites did not really shape the region’s history, in an attempt to undermine Jewish claims to indigeneity in the Land. But the duress which occasions the argument does not excuse bad history. The Land is home to multiple indigenous peoples across its long history, including both Jews and Palestinians.

I do not mean to suggest that there is not also a false centrism which attains in much American, much Christian, and much Catholic discourse, which claims to be moderate but is really in service to the far-right. Bishop Robert Barron is an example of that kind of thing in American Catholicism, for example, claiming to be a moderate but really just platforming conservatives. But I do mean to suggest that in much public discourse, the notion that there may in fact be a perspective from which multiple competing truths and pains can be equally seen and some kind of genuine reconciliation of them can be at least imagined is ruled out from the beginning. This is especially true on the Internet, where quick sound-bytes and 140 character statements and cruel but funny memes overrule complex thought as a norm.

At the very most, only the high priests and other elites in Jerusalem were involved in the death of Jesus; but see J. Christopher Edwards, Crucified: The Christian Invention of the Jewish Executioners of Jesus (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2023) for the argument that this, too, is a rhetorical device of the Evangelists to deflect blame from the Romans, who bear the real blame in the matter.

See, e.g., Alon Goshen-Gottstein, “Jewish Theology of Religions,” 344-372 in The Cambridge Companion to Jewish Theology, ed. Steven Kepnes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

E.g., Terence L. Donaldson, Gentile Christian Identity from Cornelius to Constantine: The Nations, The Parting of the Ways, and Roman Imperial Ideology (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2020).

Admittedly, too, it would require that theology generally was more important to the Jewish experience than it typically is, and especially than it is by comparison to the Christian experience. Anecdotally, as a rabbi recently told me, Jews end up talking to non-Jews about God often more than they do with other Jews.

That any particular group could hold a special pride of place in God's affections simply seems a silly assertion to me, and to my mind, misses who God revealed in Jesus Christ crucified truly is. I do not care if this offends some Jewish believers who fancy themselves as God's special chosen ones — in truth, God does not play favorites, and chooses all persons equally.

Your reflection on Novick’s Judaism: A Guide for Christians models genuine friendship between traditions. You show that true interreligious encounter means risking transformation through attentive engagement. In the tension—loving without absorbing, knowing without mastering—we approach the mystery at faith’s heart: the call to become more than we are, through the grace of genuine encounter. Tolerance can become repressive when uncritically applied, even as self-repression—like my hesitation to mention “Jesus” while praying with a Muslim friend, fearing exclusivism. Her reply: “Aren’t you a Christian?” - Thanks!