Continuatum a parte tertia.

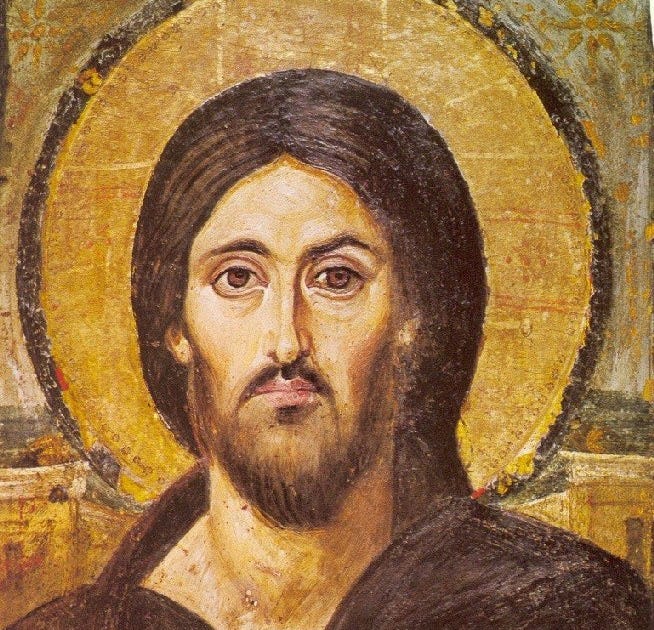

The historical Jesus, the kerygmatic Jesus, and the dogmatic Jesus are intimately linked. The event of the Jesus of history sparked the apostolic kerygma of his death, resurrection, ascension, and installation in heaven as now and future messiah; this traditional faith, in turn, became the raw material from which Jesus’ dogma…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Perennial Digression to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.