In the first of this series, I made the case that the Heilsgeschichte distorts our understanding of biblical time. The Bible does not present an absolute division of time between “this age” and “the age to come.” Instead, both “this age” and “the age to come” are but two among many in the endless cycle of ages over which God stands as creator, provider, and destroyer. Even at its most apocalyptic, biblical literature is not looking forward to an absolute end to history, but merely the next phase of a cosmic cycle which has presumably encompassed many creations and destructions.

In the second, I contended that the primary driver of eschatology is historical circumstance: people reimagine this age and the age to come in light of what’s actually going on in their real experience. Contrary to the abstract chronology of the Heilsgeschichte, no one—neither Jesus nor his followers nor the New Testament authors nor the Early Christians—is on one universal apocalyptic calendar, with one constantly ticking cosmic clock. Instead, eschatological mythemes, prophecies, and other traditions get re-received and reinterpreted in successive contexts. Eschatological time, like time generally, is relative.

And in the third piece, I charted the linearity and cyclicality of Christian eschatology: what exact historical trajectory conditioned the evolution of ancient Christian beliefs about the End, and what recurrent ideas and postures shaped Christian responses to history’s continuity. Jesus did not return in 70, 500, 1988, 2012. Whether Jesus is coming back within history at all seems doubtful from that perspective, and at least cautions us against prediction. Premillenarianism nevertheless remains a useful posture for other reasons: it reminds us that the promise of the gospel is of a world where evil has in fact been vanquished, together with injustice and war, and where good has triumphed, and peace and life reign. It keeps us hungry for the age to come.

No empire has proven eternal—Christian or otherwise. Nevertheless, postmillenarianism has its uses: it can encourage us to try and build, as far as possible, the Kingdom of God in this world. It makes us active, rather than passive, in the redemptive process. I obviously have my preferences of interpretation here: I far prefer the social democracy interpretation of the postmillenarian hope, the liberation theology interpretation, which focuses on building a world that is just and equitable and built on mercy and compassion, in which everyone has equal access to dharma, artha, and kama so as to have the freedom to pursue moksha, over the integralist vision of a restored Christendom.

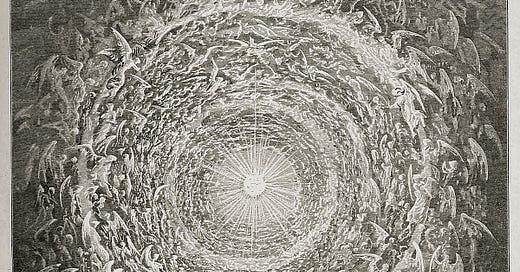

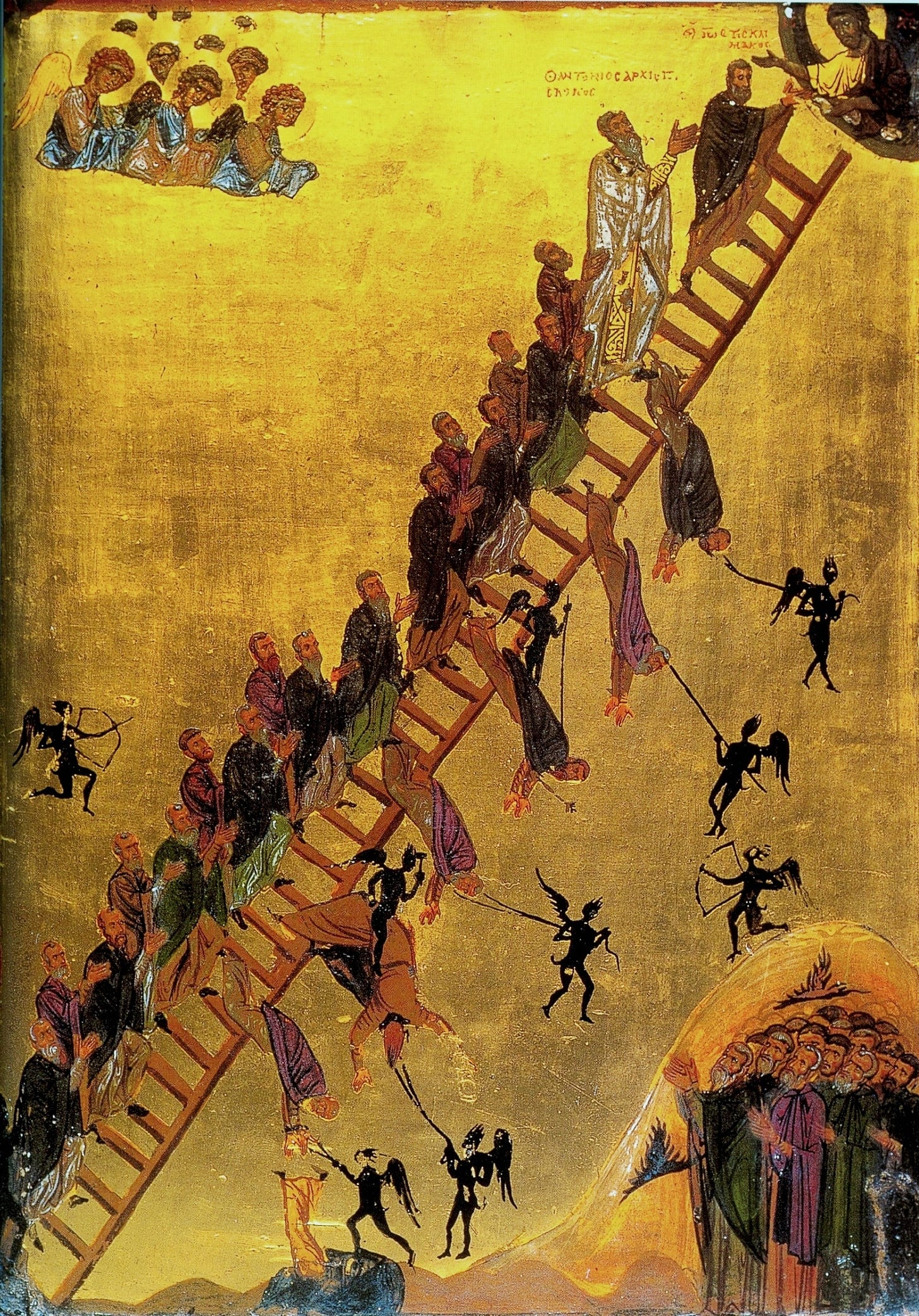

History is inscrutable when you’re living in it. Amillenarianism is a useful agnosticism, a prudent equilibrium, one that, at its most productive, points you upwards rather than forwards: there is or at least might be no coming Golden Age, at least not one that’s eternal, that won’t give way to Silver; we do not know when all the ages will wrap up (or even if they do); so the better thing to do is to seek to begin the cosmic ascent.

That is to say, deep reflection on eschatology points me towards the many senses in which something can have an “end.” I can talk about the “end” of something in the sense of its novissimum, its final outcome, but I can also talk about the “end” of something in the sense of its telos, its final purpose. So, I can worry endlessly about the end of this age, whether it has come or is coming right now or will come, or I can worry about the end of time itself, that for which time exists.

I can worry about the “end of the world,” in both the sense of when the world will end as well as for what the world exists at all.

I can worry about the end of the present state of the human condition, too, or I can contemplate the point of what it is to be human, that for which the human being is.

Eschatology of the former kind is irresolvable within history precisely because we do not stand outside of history looking in to be able to determine its “end;” and depending on how we understand providence, it may not even be the case that God himself has determined how history will end. And so the aporia naturally leads us to eschatology of the other kind—to the contemplation of my own telos, and that of the world of which I seem to be an extension, and it of me.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Perennial Digression to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.