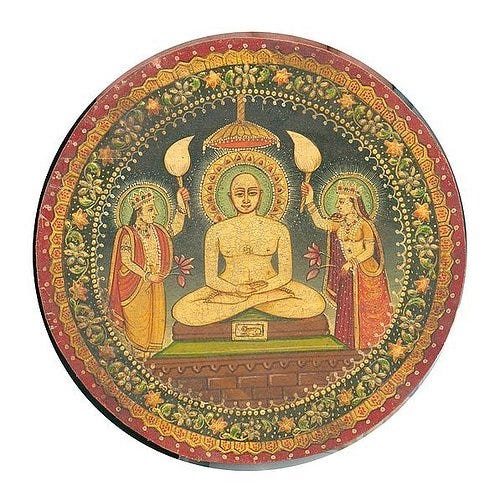

The moral superiority of Jainism to most other world religious traditions, at least at the level of theory, is obvious to me. Jainism traces itself to the life and teachings of Vardhamana, known to his followers as Mahavira (महावीर), the “great hero,” and venerated as the 24th Tirthankara, “ford-maker” or pontifical guru of the universe. Mahavira’s teachings can be broken down to three fundamental principles: ahimsa (अहिंसा), or “nonviolence;” anekantavada (अनेकान्तवाद), “many-sidedness” or even “skepticism;” and aparigrapha (अपरिग्रह), “non-possession.” Mahavira’s fundamental epiphany which made him a kevalin (केवलिन्) was the propriety of empathy for every living soul or jiva (जीव) locked in samsara, and the way that violence motivated the cycle of death and rebirth for all jivas, demonic, plant, animal, human, and divine. In this system, moksa (मोक्ष) or nirvana (निर्वाण) could only come as the result of ascetic pursuit of ahimsa and the other four vows Jains make in order to properly practice ahimsa. Anekantavada and aparigrapha are moreover co-conditional with ahimsa: to abjure from violence against other living beings requires first that we acknowledge the conditioned character of our own points of view, the many-sidedness of truth from a phenomenal perspective, and the epiphanic character of the perfect, omniscient wisdom of the kevalin; it requires also that we release our claim on other beings, including on beings that we conventionally objectify as means to our own ends. Paradoxically, the true tirthankara sees all and possesses all precisely by renouncing all, including the pretense that finitude could comprehensively grasp the infinity of beings whose intrinsically sacred lives are conditioned at each moment within samsara by their relationships—especially their relationships of victimization and predation—to every other. This comprehensive sight is a pure and perfect charity: an absolute identification with all beings in their suffering and a commitment to end it in one’s self.

This practical means of ending dukkha (दुःख), the suffering that is intrinsic to samsara, is not unique to Jainism: renunciant spiritualities within Hinduism have embraced it since Mahavira’s time, which probably stands in part behind his choice of the doctrine, and it became essential to various streams of Buddhist thought. Ahimsa is fundamental, for instance, to Classical Yoga; it is, at least, the first of Patanjali’s five yamas or “restraints,” and the other four yamas follow much the same logic as Jainism’s Five Vows:

The rules are: non-violence, truthfulness, not stealing, sexual continence and non-acquisitiveness. Of these, non-violence is never causing harm in any way to any creature. The other rules and observances are rooted in it. They are practised in order to practise it, with the aim of perfecting it. They are being expounded only for the sake of bringing about its pure form.—Patanjalayogasastra 2.30, in James Mallison and Mark Singleton, trans. and ed., Roots of Yoga (New York: Penguin, 2017), 80.

Some Buddhist texts emphasize the same idea, especially in the Mahayana tradition. Bodhisattvas are those who, we are told in the Munimatalamkara of Abhayakaragupta, “[d]ue to the power of compassion…have understood the emptiness of intrinsic nature” and “feel destitute themselves [because sentient beings] are made destitute by impermanence.”1 Bodhisattvas “wish to attain buddhahood…whose nature is one of friendship to all beings.”2 There are various things that aspiring bodhisattvas can do to attain to this state. “[T]hrough becoming constantly familiar with all sentient beings who abide in three realms,” for instance, “it [i.e., compassion] will increase.”3 But above all, such people are to take the Bodhisattva Vow: they will “promise to rescue all sentient beings,” and the aspirant swears: “I will become a complete and perfect buddha; having extricated everyone in this world from suffering, I will place them in complete and perfect buddhahood.”4 The aspiring bodhisattva abstains from nibbana/nirvana until every being may enter with them—that is, until all dukkha has been eradicated and samsara itself passes away. Whether gods or guinea pigs, this ethic demands that we suffer with the whole kosmos till the whole kosmos reaches the farther shore of nirvana.

Ahimsa is a logical corollary of any religion whose primary aspiration is universal liberation: it is logically and morally unsustainable to hope for the salvation of all beings from samsara or sin or hell or whatever while also preying upon them, in whatever way. Respect for the intrinsic dignity of every creature requires that one forsake the claims we habitually construct to justify our need to exploit the Other. So Jains are historically vegan or lacto-vegetarian, as are most schools of Buddhism, as are many streams of Hinduism, particularly bhaktic, yogic, and Vedantic expressions: because animals, too, are souls trapped in samsara and conditioned by karma and dukkha, their exploitation is not morally justifiable. For all of these systems, too, ahimsa relativizes the significance of the devas: Mahavira had no use for Vedic sacrifice, and neither did Sakyamuni Buddha, both of whom lived in the evanescent glow of Vedic culture in the period when it began to register as spiritually dissatisfying to the broader population of the subcontinent. Yoga and Vedanta also relativize the gods: as for Jains and Buddhists, they exist, but they are as much part of the system of death and rebirth as anything else, subject to the same laws of righteousness and ascetical aspiration as any other creature. True, both Yogins and Vedantins relativize the gods in a way that Jains and Buddhists do not: by reference to a thoroughgoing classical theism, that is, in which the devas all severally manifest different qualities of Brahman saguna, “Brahman with qualities,” also known as Isvara, the Supreme Lord or God. Isvara may be identified with the supreme deity of a particular bhaktic culture, like Visnu or Siva, or may be generalized; but to have God as the object of communion was, for philosophically-minded Hindus as for Jews, Christians, and Muslims further West, freedom from the tyranny of the gods, benevolent or malevolent. Ahimsa is a kind of cosmic rebellion against the divine order of the universe which, for all of its beauty and sublimity, seems very much beholden to what David Bentley Hart once called “the inescapable circularity of natural existence,” which engenders “something very like an absolute alienation of human consciousness from the rest of the natural world.”5 It is not accidental that the great sannyasin sages of the subcontinent were thought to be both rebels against the sacrificial system the gods require and/or teachers of the gods themselves, then: the gods, too, are conditioned by avidya (अविद्या), “ignorance,” concerning the nature of ultimate reality as evidenced both by their finite (albeit superior) form of existence within samsara as well as the worship they mistakenly arrogate to themselves. Jain and Buddhist transtheism redirects that worship nowhere, but seeks through the embrace of compassionate ahimsa the liberation of all beings, including the gods, from the violent cycle of rebirth through the acquisition of appropriate knowledge, which requires the letting go of our favorited concepts and collections; Yogins and Vedantins redirect worship away from mere gods to God. Ahimsa in a classically theistic system is the acknowledgment of God’s infinite presence in and to all finite beings, regardless of their place in the cosmic hierarchy, and therefore the supreme relativity of that hierarchy from an objective point of view: the devas may well be superior to us from the finite perspective, but from God’s perspective, all things are his creatures, expressive of his attributes, devas and dust mites alike.

Ahimsa as an ideal, of course, appears frequently in Indian esotericism and textual tradition, and as an ideal of religious communities and renunciants of varying kinds across the subcontinent, but it has at many points in Indian history not been apparent as an explicit value at the social and political level. The Mauryan emperor Ashoka the Great (268-232 BCE), for instance, promoted “non-harming of living beings” in his Edicts, but he also acknowledged his own slow-moving progression towards vegetarianism, and he did not finally abolish his military or radically reform the fundamental structures of his society to eliminate violence therefrom altogether.6 Jews, Christians, and Muslims could hardly take him to task for this. The Tanakh is arguably, at least on one tradition of reading it, one long story of the way that God calls Israel into being to help him rectify the violence of the world order, but how Israel as a people struggles in vacillation between a thoroughgoing renunciation of cosmic violence and complicity with it, sacralizing and abhorring, glorying and reviling the bloodshed which can be found in the Torah and the Former Prophets. Early Jewish literature seems generally predisposed towards the notion that violence is the exclusive prerogative of the divine, who executes or will execute justice on the wealthy kings of the world who oppress Israel’s remnant; this at least is a signature hope of apocalyptic texts, and it becomes a fundamental principle of rabbinic halakha much later. Hence the famous dictum of Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:9//Yerushalmi Tractate Sanhedrin 37a, “Whoever destroys a soul, it is considered as if he destroyed an entire world. And whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world.” It is in this thoroughly Jewish, apocalyptic tradition of martyrdom and righteous suffering that Jesus should be understood. He has a clear ethical preference for ahimsa: he commands his followers to abstain from violent resistance and reaction to those who would do violence against them (Matt 5:39); he rebukes the disciples who seek to arm themselves as he comes to Jerusalem (Lk 22:38) and tells Peter to put his sword away and not defend him, since those who live by the sword also die by it (Matt 26:52).

Some early Christian groups concluded from the way of the cross the necessity of nonviolence not only against humans—which was absolutely mandatory in the first centuries7—but also against animals (e.g., Pseudo-Clementine Homilies 7.4); yet these groups were, on other grounds, sometimes ostracized as heretical by emerging orthodox writers. In general, the meat-eating culture of Greco-Roman antiquity, which was largely confined to the sacrificial banquet, was transfigured in the absence of actual animal sacrifices offered in temples to a periodic consumption of meat in festal seasons for Jews, Christians, and Muslims. This periodic meat-eating was nothing like our own contemporary culture of factory farming and constant feeding on animal flesh: it was born from a culture where mutuality between humans and animals was still necessary for survival, and where rules of ritual purity surrounding slaughter, preparation, and consumption for all Abrahamists or Adonaistic religionists (whichever terminology one might like) were still active. It would take many centuries in Eastern and Western Christianity alike for consciousness of such rules—for instance, prohibitions against the consumption of blood—to fall out of practice and then, finally, to be entirely reversed in Western canon law (as in Cantate Domino). Sure, Orthodox still abstain from meat on Wednesdays and Fridays, and the rigorous through the four great fasts of Lent, the Apostles, the Dormition, and the Nativity; Catholics theoretically are obliged to do so on Fridays throughout the year and particularly during the Lenten season. But once even ordinary, licit meat-consumption had particular rules around it for all Christians, rules which in their essence respect the life of the animal and its meaning, which for rabbinic civilization constituted one of the fundamental distinctions between the pagan and the Noachide or ger toshav or tzaddik. And the lifestyle of Eastern monastics still witnesses to the Tradition’s ideal: they, like Adam in the Garden, abstain from meat to try and cultivate the theoria of the Creator in all creatures.

That encompassing vision is the only real conclusion one can reach if one believes in the God that Christianity claims to—a God who is infinitely simple and purely actual, and therefore who is Non Aliud than the world of his creatures, but is instead “the All” (LXX Sir 43:27), the one “in whom we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28). For to know that God as the God revealed in Christ is to see all things with double vision: to see, on the one hand, the divine beauty which they manifest and, on the other hand, the way that their finite existence in this kosmos is conditioned by suffering. Samsara need not be thought an exclusively Eastern doctrine, at least if by it we acknowledge minimally that all creatures are ensconced in a fallen state that is cyclically reinforced by predation and victimization, and that most creatures do not see from an omniscient vantage so as to be even remotely aware of the worlds whose churning destruction they depend upon for life. A deep level of pity that true theoria should bring us is the awareness that most beings live ignorant of the systemic violence with which they are complicit, which conditioned their own existence and which will someday bring it once more to an end; and even this knowledge often just inflicts more suffering, more dukkha, for it stokes both sympathy and hunger, tears of violent rage and sorrowful resignation. There are of course beings whose intentions towards the world are malice; there are creatures that delight in gore. But our greatest spiritual traditions teach that a creature who can find such delectability in horror is wounded more deeply still by its own avidya: ignorance of the Truth, as Christ taught, is the cause of sin (Jn 8:34). At one and the same moment, the Cross reveals the ignorance of the violent kosmos as well as the logos of the peaceable kingdom of creation; the true saint is the one capable of upholding that absolute ahimsa in the face of the fathomless violence of the marred universe.

I said this was a self-castigation; it is. I find the prospect of becoming vegetarian difficult, for emotional rather than for primarily nutritive reasons: an upbringing from the lower and lower-middle class has meant that all the meals and acts of koinoniai with which I have had the deepest connections are based on the cheap, available meats that made them possible. Giving up on dining meat, from antiquity to today, has social costs: what meat one can or will eat, if any, has divided entire peoples, and just as dramatically, families. Diet is a spiritual thing: it reflects a whole culture, worldview, and orientation toward the world. Changing one’s culinary options is never a singular or isolated thing: it would require on my part some degree of mission or at least apologetics to those in my immediate sphere. Whether one adopts kashrut or abstains from eidolothuton or observes fasts or enlarges the range of exotica one is willing to dine on, fellowship expands and contracts, twists and tapers to these decisions. To some extent, my fear of the shifts that sort of move would create is a product of my place in the world. I do not have the freedom of a monk or a bachelor; I am a husband and a father living in a culture where eating meat is normative and where options for herbivorous living, while growing in some places, are still fewer than they could be. I have extended family and relations whom I most often see, if at all, in the context of communal meat-eating. It does not quite matter what it will say to them to refuse to dine on their food: it is the fact that it will say something to them at all that can sometimes paralyze me.

This is castigation, not justification: it is one of numberless reasons that I am no tirthankara. But perhaps there is yet hope. Though he struggled with it at first, Ashoka seems to have ultimately mastered at least this most basic requirement for a life of genuine ahimsa; plenty of people have followed suit. But it is a beginning, not an end: we cannot achieve a reciprocal consciousness of the divine in all things as long as we are still feasting on fellow beings whose rationality is not really very different from our own, but that is not to say that abstinence itself is maximally sufficient to so clearly see. After all, ahimsa requires aparigrapha: it takes a detachment from the stoicheia of life that is effectively impossible for the householder to truly not resist the evil man, and an otherworldliness not possible for the kosmikoi to refuse to defend the weak. Indeed, the wisdom of Jewish and Christian prophetic and apocalyptic texts in calling for divine violence against the wealthy and the powerful acknowledges the luxury inherent to ahimsa: it is easy enough to idealize peace when peace is not being enforced by one’s own exploitation. Ahimsa is both remedy and deflection, for example, for the current ecological crisis: the same compassion we must cultivate for all can easily lull us into a false sense of security about the urgent cost, human and not, of climate change.

So perhaps preface to the most rudimentary ahimsa is Ashoka’s own advice: to exercise compassion for those, including ourselves, who desire to overcome our addictions to flesh and find it a struggle. Part of anekantavada is the realization that not every being is in a place of equal ability to take up the life of askesis, and compassionate appreciation for every being doing what it is capable of doing; like the widow’s mite, we must believe that God accepts what we are realistically capable of as the genuine offering of our lives (Mk 12:41-44). With regard to human beings, this principle of “many-sidedness” means accepting the reality of life: that people are complicated; they are complicated more for reasons they do not choose than for those they do, since their choices are at every level conditioned by the circumstances into which they were born and by which they were reared; that their worst sins and their greatest merits are all always, already contained within the divine mercy, however accountable they may be within contingent history for their real violence and whatever rewards await their cooperation with divine grace. Like the Jain or the bodhisattva, as Christians we must seek—however long, across however many ages—the liberation of every being from sin’s damage; but we cannot even begin to desire this until we have learned to understand beings on their own terms. And so the double vision of all things in God and all things in their fallenness can only be resolved in the tertiary epiphany of love, that love which alone knows all.

Donald S. Lopez Jr., Buddhist Scriptures (New York: Penguin, 2004), 389.

Lopez, Buddhist Scriptures, 389.

Lopez, Buddhist Scriptures, 390.

Lopez, Buddhist Scriptures, 390.

David Bentley Hart, “Death, Final Judgment, and the Meaning of Life,” in The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology, ed. Jerry L. Walls (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 477-478.

On Ashoka, see Sonam Kachru, “Ashoka’s Moral Empire,” Aeon (2020).

See Michael G. Long, ed., Christian Peace and Nonviolence: A Documentary History (New York: Orbis, 2011).

Through the violence he suffered he ends all violence. By his death all death ends. Samsara has met its conclusion. The resurrection has broken the cycle of death and rebirth! The age of Kali yuga is at the end! The path of veganism can become a prophetic sign for those awaiting the resurrection. I join you in your castigation. Thank you for the post.

It might help you to consider that in many Asian traditions, laypersons are not expected to become absolute vegetarians, or at least not overnight. In China, for example, Buddhists might choose to be vegetarian on certain lunar days. A good friend of mine in China not only eats vegetarian on certain lunar days, but he chooses to not eat beef at all. Just by doing this, he's already reducing his impact. Buddhists have a more 'evolutionary' view of ethics. He's not a vegetarian, but in his community's eyes, O Lordy he's tryin'!